In Step 16, we consider the effect of those acts and words that that happen without any preparation or forethought. While a spark of spontaneity may be inspired by serendipity and work out for the good, a wholesale lack of reflection will land us in the soup. We explore Kairos, the opportune moment, in order to remain in better order, and discover the cause of unhappiness that lies in self-dramatisation and an inability to abide by our guiding principles.

§. Consider well before you act,

So that you don’t commit foolishness.

Only an unhappy person acts and speaks without reflection.

Accomplish those things that will not make you sorry afterwards. §

-Verses 28-30

FORETHOUGHT AND AFTERTHOUGHT

Throughout this course we have taken each lesson as a step along the way. Yet we seldom think of the track that we have taken as one that has a discernable shape through time. Were we able to take a bird’s eye view, we might think differently.

‘The future is composed of the past—that is to say, that the route that a person traverses in time, and that we modify by means of the power of our will, we have already traversed and modified; in the same manner, using a practical illustration, that the earth describing its annual orbit around the sun, according to the modern system, traverses the same spaces and sees unfold around it almost the same aspects: so that, following anew a route that we have traced for ourselves, we would be able not only to recognize the imprints of our steps, but to foresee the objects that we are about to encounter, since we have already seen them, if our memory has preserved the image, and if this image was not effaced by the necessary consequence of our nature and the providential laws which rule us.’ From Fabre d’Olivet’s translation of Golden Verses

However we have viewed our journey to this very moment, one thing resonates beyond the moment into our future: the turning points when foresight or forethought was not adequate for the decisions that we took:

‘Of all the things that happen against our will, even the most painful are alleviated by foresight. Then, thought no longer encounters anything unexpected in events, but the perception of them is dulled, as if it were dealing with old and worn-out things (Philo of Alexandria On the Special Laws ii,, 46, 6-10).

This kind of rational foresight, which we’ve already met, was a speciality among the Stoics, whose idea of ‘erasing the representations’ in our imaginations prevents from hurtling headlong into a romantic fiction and encountering disappointment. By confronting the possibilities that lie ahead we are not taken by surprise.

Of course, we all make mistakes, miscalculations, and are rushed into decisions that, on reflection, we should have avoided, but Hierocles speaks kindly of our errors and points out that ’when we have fallen from being good, let us at least get hold of becoming good and, with well-considered regret, accept being set right with the divine. This self-conversion is the beginning of philosophy.’ (GV, XIV 10)

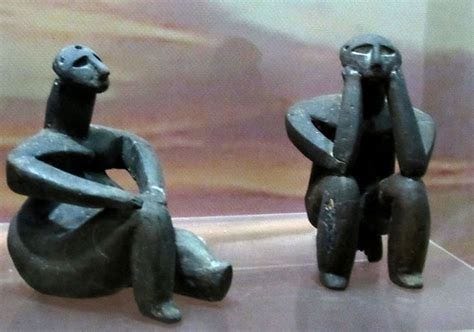

Here we are dealing with Forethought and Afterthought, who of course, are both installed in the Greek pantheon as Prometheus, the god of Forethought, who was brought into being alongside his brother Epimetheus or Afterthought. Together, these Titanic brothers were charged with the task of populating the earth with animals and people, but in his work, Epimetheus soon ran out of gifts after his creation of animals: he had imbued some with flight, others with the ability to burrow, some were given armour, while others had the ability to run away. But he had nothing left with which to endow the humans that his brother Prometheus had formed.

Seeing the poor bare human, without either tools or fur, vulnerable to the predations of all, Prometheus had to do something to ensure human survival and went on a raid to the realm of the gods Hephaistos and Athene, whose mechanical tools and cunning arts he stole from heaven to give to his creation. This is how humans acquired the craft of fire and the inspiration of art, thus receiving the means to sustain their lives. The corollary of this is well known, for Prometheus was punished for his temerity by Zeus, taken to be pinned to the rock where an eagle came daily to peck at his liver, until he was rescued by Heracles in a yet distant future.

The coda for humans was the story of Pandora. Zeus called Hephaistos and Athene to create a maiden and imbue her with every gift and grace. The maiden Pandora, whose name means ‘All the Gifts,’ was sent to earth as a gift for Epimetheus. Now, he had been warned by his brother Prometheus to beware of accepting any gift from Zeus lest it be harmful to humans, but since his brother was already chained to his rock, Epimetheus took the gift of a great jar. Inside it, Pandora struggled off the lid and emerged, and with her, all the ill-will of Zeus towards humanity, leaving only hope in the jar, says Hesiod.

This very difficult myth outlines the forethought and afterthought themes for us to ponder. It sits badly within Neoplatonic thought, since the divine has no grudge towards humanity and it is clear that the myth of Pandora has something not quite right in it, since she is named for all the gifts, not as a vengefulcurse to humanity. We have only Hesiod’s account and we have lost any earlier notion of the blessings of those gifts and how they are distributed among us.

What is clear is that all the gifts of humanity come with their own terms and conditions, so that we need to exercise the forethought of Prometheus and not borrow any help from the afterthought of Epimetheus. What we need for that task is Kairos or the timely moment.

KAIROS – THE TIMELY MOMENT

Kairos is ‘the right moment’ for things, actions and words. We are all masters and mistresses of the doorstep word, whereby we can think of just the right thing to say, only that those trenchant words arrive anything from ten minutes to ten hours later than they were needed! In his Kaironomia (1983), E.C. White defines Kairos as the ‘long, tunnel-like aperture through which the archer's arrow has to pass,’ and also as the moment ‘when the weaver must draw the yarn through a gap or shed that momentarily opens in the warp of the cloth being woven.’ This opening is where we hope to place ourselves for living in harmony with the cosmos.

The Pythagorean life-style which we are uncovering with the help of the Golden Verses, was about finding harmony in the present moment and remaining faithful to it. Taking time to understand what is at stake in any situation is subject to three aspects of good counsel or the sound judgement that lies within us. Hierocles tells us:

‘There are three functions of good counsel: firstly, the choice of the best way of life, secondly, the practice of what has been chosen, and thirdly, the strict adherence to what one has correctly trained oneself within.’ (GV, XIV, 2). This sound judgement involves, ‘the prior reasoning which lays the foundation of action; then the reasoning which accompanies and adjusts the action; lastly, the reasoning which follows the execution of the action, and which examines each action we have performed, and judges whether it was well done.’

This essential examination was a central part of Pythagoras’ well-lived life, and also of all philosophers. It was a focused recollection that could be engaged by many different methods, which we would all recognise as the basis of a daily spiritual practice. Pythagoras bade us:

‘look up at the sky before Dawn….. and meditate on the constellations that are constant in their relations with one another and unswerving in their duty – holy, pure, and naked - for no star wears a veil.’ (Iamblichus VP 92)

But Marcus Aurelius spoke of his own morning practice very differently, in the following terms, bidding us to cut ourselves free from our thinking, and from everything others might say or do; to cut ourselves free from what you have said or done in the past, and from the things you might say or do in the future; to cut yourself free from all that does lie under your control and which stirs up the waves of violent emotion in you. Marcus Aurelius Meds XII, 1-3)

These two instructions seem almost at variance, but they are both about stripping things down to essentials, and concentrating on what keeps us upon our road. Rejoicing in the opportune moment, we can say with Marcus,

‘All that is in accord with you is in accord with me, O World! Nothing which occurs at the right time for you comes too soon or too late for me. All that your seasons produce, O Nature, is fruit for me. It is from you that all things come; all things are within you, and all things move towards you.’ (ibid. IV, 23)

The many projects that we have planned without due forethought and have crashed and burned are testament to our lack of forethought. We are not lone individuals in this foolishness. Those things which are perpetrated by governments in the public interest and which prove fruitless, are no different, although these failures may have longer and more serious ripples which reach down into generations yet unborn, due to foolish unpreparedness and lack of forethought for the consequences to come – a fault of short-term rule in democracies where first one side of the political divine, and then the other, changes policies that should rightly be determined for the good of all before being voted into law. If only a sense of Kairos , supported by Forethought entered into our governmental systems.

For ourselves, we have to remember what Epictetus advizes:

‘Purify your judgements and say, ‘you are training yourself day after day, not that you‘re acting like a philosopher, but rather that you’re a slave on the way to emancipation.”’ (ED 4:1 112, 113.) That freedom remains our goal.

HOW DOES UNHAPPINESS ENTER INTO THINGS?

You may wonder why unhappiness is attached to lack of forethought. In Neoplatonism, foolishness is usually associated with deviation from our prime condition of harmony and a betrayal of our oneness with the divine. Pursuing foolish aims, acting without forethought, inevitably brings us into a state of disappointment and, possibility, humiliation.

Marcus Aurelius spent a good deal of time considering what is an appropriate action. It was not enough for him to just to want to do good, but rather it was dependent upon what precise actions or duties he should take. He suggests to us,

‘On the occasion of each action, ask yourself this question; what is it to me? Will I not regret it? In a short time, I will be dead, and everything will disappear! If I now act as an intelligent living being, who plays himself in the service of the human community and who is equal to God, then what more can I ask?’ (Marcus Aurelius, Meds,IV, 32, 5)

By ‘equal to God’ here, Marcus is meaning ‘when he is in a harmonious condition’ and therefore resonant with the divine, lest we imagine he is thinking hubristically. Someone with a large capacity and will to act dutifully in his position of emperor has a larger responsibility than you or me, of course, but every person, in whatever position they occupy in life faces the same challenges. The outcomes of our actions, when they are supported by a genuine will to do good, can be infused with a sense of dancing with the divine, which is not the same as a performance or entertainment, as Marcus tell us:

‘the rational soul achieves its proper end, wherever the limit of its life may be. It is not as in dance or the theatre or other such arts, in which - if something comes along to interrupt them - the entire action is incomplete. The action of the rational soul, by contrast – in all of its parts, and wherever it is considered – carries out its projects fully and without fail, so that it can say: “I have achieved my completion.” (ibid. XI, 1, 1-2)

But elsewhere, Marcus writes, ‘you must set your life in order by accomplishing your actions one by one; and if each of them achieves its completion, in so far as it is possible, then that is enough for you. What is more, no one can prevent you from achieving its completion.’ (ibid. VIII, 32).

This very sense of being unable to complete or accomplish our aims, the frustration of an imagined aim by a terrible thwarting can lead us into entering into the drama of ourselves, where our predicaments can lead us into self-dramatization. This is precisely what the Stoics meant when they tried to ‘erase the representations’ of the imagination. From a more modern perspective, we can see this problem of imaginative captivation as a form of ‘watching ourselves acting’ as if we were actors upon a stage or tv, whereby we get caught up in the intensity of how the action is unfolding, and so we abandon our good sense and allow ourselves to become the instrument of yet worse outcomes.

Neoplatonists frequently invoked the example of Medea as one, ‘who had betrayed her nearest kindred because of a wayward love, given herself into the hands of a stranger (Jason), and then, neglected by him, believes herself to be suffering unendurable things… She tries to remedy evils with more evils,’ which include the killing of her own children by Jason and the murder of his new wife. (GV. XIV, 12) Both Medea, and Agamemnon of the Trojan Wars, are held up as those whose emotions betray them into unwise, hasty actions and furious words that lead them further astray. Hierocles speaks of both them:

‘All life without thought is like this, tossed here and there by opposing passions, despicable in its pleasures, pitiable in its sufferings, rash when it is bold, and dejected when it is fearful. In short, as it is without a share in any upright thought supplied by good council, and changes its mind along with its fortune.

Now, so that we may not be infected by such dramas, and act and speak thoughtlessly, let us use right reasoning as our guide in everything, and fulfil the Socratic saying: “that I am able to obey nothing that belongs to me except the reason that, on reflection, appears to me to be right.” What belongs to us, though not what we are, serves our reason: spirit, desire, sense perception, and the body itself, that is employed by these faculties for use as an instrument. We must not obey any of these except as Socrates says, right reasoning: that is, by the part that is rationally disposed by nature. For it is this element alone that can distinguish what must be said and done. And to obey right reason is the same as to obey a god.

Since the rational sort of people are well-endowed with their own illumination, they want what the divine determines, and the soul that is disposed towards God comes to cast its vote with God, looking to the divine, and to the light in whatever it does; but in those who are irrationally disposed, the soul is randomly and by chance carried away to the godless in the dark, because the soul has fallen away from the only measuring line of the morally beautiful: intellect and the divine.’ (ibid, XIV, 15-16)

The saying by Socrates, referenced here, is taken from Plato’s dialogue Crito 46b-6, where Socrates has been condemned by the state, and his friend Crito comes to beg him to escape from prison; Socrates refuses, despite Crito’s well-argued request to flee, because his reason shows him a greater obedience. Crito, like most of Socrates’ companions and friends, enter into the drama of his imprisonment and impending execution, but Socrates is not caught up in all that. He holds to the advice of his daimon.

Ultimately, as Epictetus says, ‘There is only one path to happiness, and so keep this rule to hand both morning, noon and night: the rule is not to look towards things which are out of the power of our will, but to think that nothing is our own, and to surrender all things to the Divinity, to Fortune; to make them the administrators of these things, whom Zeus has appointed to for this task; devote yourself only to that which is your own, which is free from hindrance; and when we read, to refer our reading to this end only, as with all our writing and our listening.’ (ED 4:4, 39-40)

Happiness comes from being in harmony, not when we are displaced from the factory settings of our own being, not when being forced or persuaded to act against our nature, and certainly not when we forget ourselves and perpetrate actions or utter words which become banana skins which will make us skid off of path. When we bring a sense of service into our actions, we rediscover that harmony, as Marcus lyrically reminds us:

‘Your only joy, and your only rest, is to pass from one action performed in the service of the human community to another action performed in the service of the community, together with the remembrance of the divine.’ (Marcus Aurelius, Meds, VI,7)

§ CONSIDER:

· Hierocles tells us that, ‘Self-conversion is the beginning of philosophy,’ whereby we take time to consider our words and actions. In a few weeks, we will be led to the central tool of this Pythagorean process of self-clarification and true understanding, but until we reach that step, take time at the end of the day to uncover the day’s events, and begin to stabilise and convert your understanding of why and how things fell out. Without blame or guilt, and with the same attitude as someone tuning an instrument to pitch until it sounds true, take time to find the disparity between what you intended and what emerged from the day, beginning to note the recurrent patterns.

· By what actions or words do you serve the community?

· Hierocles says that ‘to obey right reason is the same as to obey a god.’ Meditate upon the nature of that divinity and how you interact with it.

MEDITATION

In this meditation, Iamblichus considers the nature of Kairos, the right or opportune time as based upon an order and recognition of the guiding principle of our lives.

‘The use of the opportune time, then, is a complex and many faceted art. Four of those who become angry and furious, some do it appropriately, others inappropriately; and again, of those yearning for, desires, and eager for whatever it might, appropriateness accompany some, but inappropriateness others. The same goes for all other emotions, actions, dispositions, associations, and conversations. Appropriate is to some extent teachable and subject to calculation, and thus admits of systemic treatment, but when generally considered and simply put none of these exist for it. In accord with, and almost concomitant with the nature of the opportune time, are such things called, the right time, the fitting, and the appropriate, and anything else which can be akin to those they asserted that the first principle is in everything one of the things most honourable, equally in knowledge and experience, in generation, and also in a household, a city, an army and in all such organisations.

But the nature of principle is difficult to discern and survey in all the areas me for in the sciences, when looking at the parts of a study, it is a task for no ordinary intellect to understand and to form a right judgement as to what the principle of these is and it makes a great difference, and is almost crucial importance to the success of the whole enterprise to understand the principal correctly. For nothing, in a word from there on comes out right when the true principal has not been recognised. The same goes for principal in its other sense such as a ruling principal for neither a household nor a city is ever well managed were not voluntarily subject to the rule and authority of a genuine commander and leader.

For authority to arise it is necessary for both, the ruler and those rule, to be equally willing. Just as they said that teaching is correctly imparted when it takes place voluntarily, and both the teacher and the student are willing. For if either of the two resists in anyway, the proposed work can never be Dooley completed. So then, himself approved of obedience to rulers as good, and also submission to teachers, and by his deeds he presented greatest proof of this as follows. He travelled from Italy to Delos, in order to nurse his former teacher, Fides of Cyrus, who had succumbed to the disease recorded as morbus pedicularis (prurigo), and finally to bury him. He remained until his death and performed the funeral rights for his master. So greatly did he value his teacher.

-Iamblichus VP, lines 178-184.

An excellent explanation of Karma, Caitlin. I loved the Forethought and Afterthought that made me think also of the very power of Thought itself and the influence of inner and outer thoughts and the senses of Silence and Speech. Zeus giving the power of Hope within the Box of our mind for example not only gave Hope to the Virtues but also to the Vices, to Humanity in whatever state or time it is in existence when the Box may be opened. I absolutely loved this entire work of yours and the philosophy of the ancestral teachers. The speed of thought and accuracy is our safety net at the present time. Meditation is a way of cleaning the mind also so that Hope has a chance, I think. Thank you for this post. I loved it. Xxx.