In this post we reach the end of Part 4 which has been about the power of words – spoken, applied, received - and we are about to approach a most extraordinary changing of the guard. Our opinionated views on what we think we know often betray us and we find ourselves in deep waters where we do not how to swim. The very pleasant life that we can enjoy still remains closely tied to the very first steps on this course, which will never lead us astray and which will always reveal themselves to us through our own primary experience.

§ Never do anything which you do not understand

But learn all that you need to know,

So that you will lead a very pleasant life.§

- Verses 31-32OPINIONATED ARROGANCE

What do we know and what we do not know? Presuming upon knowledge when you do not actually possess it was regarded by philosophers as ‘opinionated arrogance’, and we are all guilty of it from time to time, presuming upon our opinion rather than upon any firm knowledge. It can lead us inexorably into the quagmire of words from which there is no extraction, as many have discovered.

Actual ignorance and not knowing a thing are not so bad, but ‘double ignorance’, as propounded by Socrates is something else – that is when we don’t know a thing and yet have the audacity to claim that we do. By compounding our lack of knowledge we teeter uneasily on the weight of our opinion.

Socrates at his trial relates this story against himself. He tells how an impetuous friend of his, Chaerephon, once visited Delphi – the great oracle of Apollo. ‘He made so bold as to ask the Oracle this question; and, gentlemen, don’t be disturbed at what I say; for he asked if there were anyone wiser than I! Now the Pythia replied that there was no one wiser. And about these things his brother here will be your witness, since Chaerephon is now dead. But see why I say these things; for I am going to tell you whence the prejudice against me has risen. For when I heard this, I thought to myself “what in the world does the God mean, and what riddle is he propounding? For I am conscious that I am not wise either much or little. What then does he mean by declaring that I am the wisest? He certainly cannot be lying, for that is not possible for him.”

Socrates continues: ‘And for a long time, I was mystified as to know what he meant, then with great reluctance, I proceeded to investigate his words further. I went to one of those who has a reputation for wisdom, thinking that there, if anywhere, I should prove the utterance wrong and should show the oracle, “this man is wiser than I, but you say I was wisest.” So I made an examination of this man - I do not need to call him by name but it was one of the public men (Sophists) – and I found by conversing with him, that this man seemed to me to be wise in the eyes of many other people, but especially to himself, but he proved not to be so wise; and then I tried to show him that, while he thought he was wise, but he was not.

As a result, I became hateful to him and to many of those present; and so, as I went away, thinking to myself, “I am wiser than this man; for neither of us really knows anything fine and good, but this man thinks he knows something when he does not, whereas - as I do not know anything - I do not think I do either.” I seemed then, in just this little thing, to be wiser than this man, at any rate, in that what I do not know I do not think I know either.” From him I went to another of those who were reputed to be wiser than he, and the same thing seem to me to be true; and there I became hateful both to him and to many others. After this then I went on from one to another, perceiving that I was hated, and - grieving and fearing - but I nevertheless thought that I must consider the god’s business of the highest importance. So I had to go on investigating the meaning of the oracle, to all those who were reputed to know anything. And by the dog, man of Athens, it was the same…’ (Plato Apology 21 a-e.)

Wherever and whomever Socrates asked, everyone grew inflated and then resentful at him, because he could not help showing them the folly of their assumed wisdom.

Seeking knowledge is wonderful, but acting upon knowledge that has not become your own is a disaster. Half-knowledge, or having some acquaintance with a technique or body of wisdom leads to half-baked results and usually embarrassment. ‘Being ambitious,’ Pythagoras, said, ‘is all very well, but the ambitious need to cast themselves in the role of athletes who compete for victory crowns at the games: these sportspeople do not compete to harm their fellow competitors, but rather to win victory for themselves. Ambition leads to casualties. Similarly, if you claimed to be an active force for good in your community or in public life then, for goodness’ sake, at least be as good as you claim to be.’ (Iam VP 9, 49)

Unfortunately, our ambition to get ahead leads us off into dangerous ground, and we cannot just be glad that someone else has a skill or a form of wisdom that can enrich the whole community. We humans always have to be top-dog! Hierocles comments, ‘through ignorance of better things, one necessarily becomes a slave of the worst, from which there can be no other way to freedom done by remembering to turn to intellect and god.’

Attending to our own nature and not trying to influence others is also important, because much unhappiness results from our own attempts to control others and persuade them against their better nature:

‘Remember well that no-one has power over another person's ruling principle. We cannot wish for anything else than that which was our own. And what is this? We cannot try to make people may act according to their nature; for that is a thing which belongs to another; but while others are about their own affairs, according to their choice, we ourselves must conform to our own nature and live by it. It is only by doing what is our own nature that others may also be in a state conformable to nature. For this is the object always set before us by the wise and good person.’ (ED 4:5,5)

How can we become such a being?

AUTHENTICITY AND APPROPRIATION.

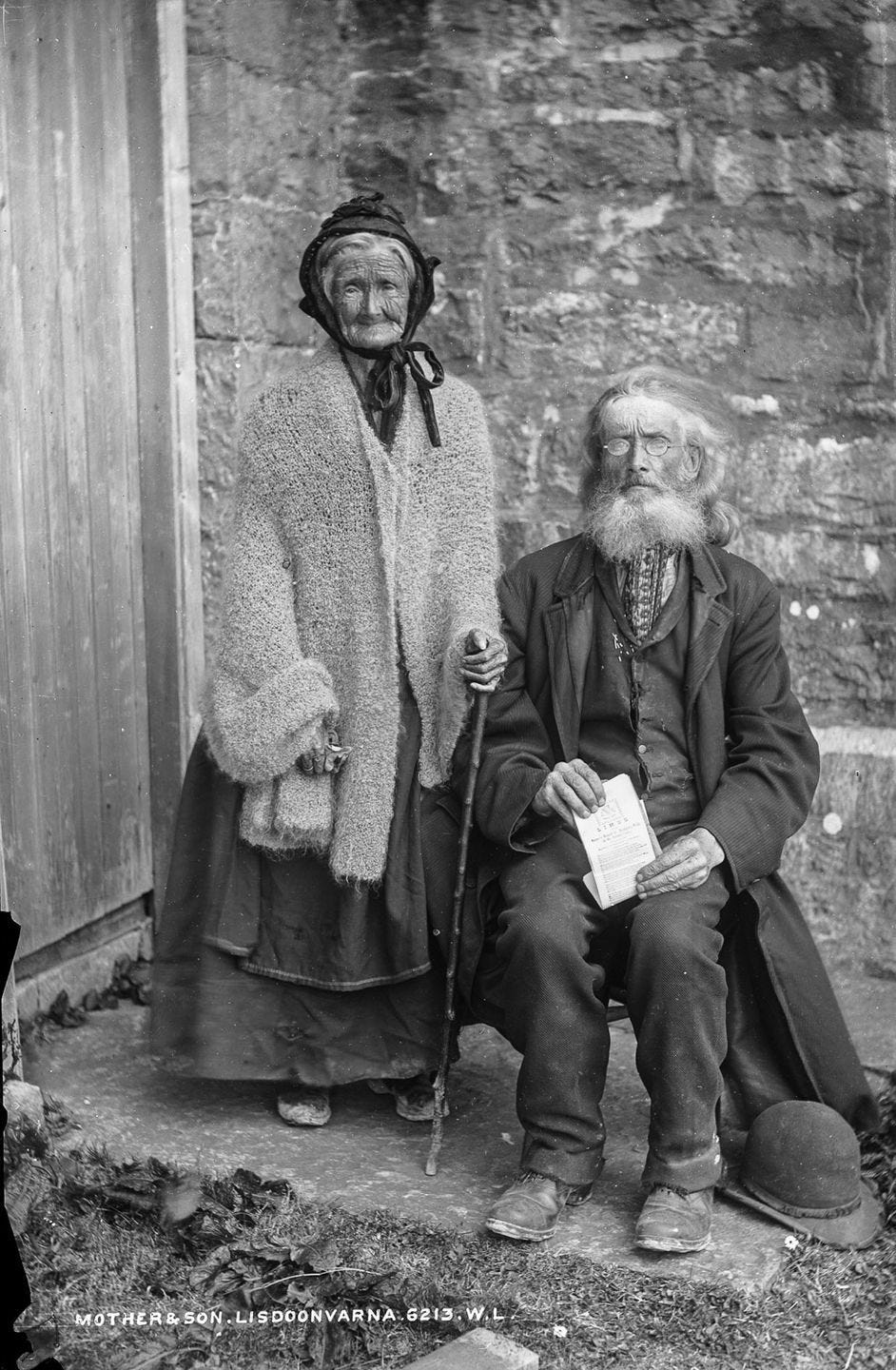

Authenticity is now a big issue among people in the world of spiritual education. Being authentic to yourself, and also being authentic in your practice is an essential. But when you do not have your feet grounded in a tradition, there are sometimes problems. For example, it may seem that the outcry against the appropriation of indigenous ways is a lot of fuss about nothing, but that is because most people do not understand that the wisdom of indigenous cultures is the inheritance of a line of revered ancestors. What may seem to everyone as ‘common rituals that anyone might share in,’ are regarded by indigenous peoples as regalia; for them, the songs, rituals, customs, costumes, and dances are not just ‘set-dressing’, but actual instructions that, of themselves, teach and instruct the descendants. These often come with protocols that we do not see, understand or value and which, like the small print on a contract, act as safeguards and boundaries.

From my own tradition, I can instance a particular example. When the 19th century story-collector US ethnologist and folklorist, Jeremiah Curtin, himself an Irish speaker, went around Ireland collecting stories, he got to know many of the older people who were tradition bearers. On his return to Ireland for a further field trip, he looked up some of these people once again, asking kindly after them. He learned that one of the elderly women from whom he’d collected a good deal had been unwell directly after he had visited: ill enough, that is, to have been admitted to hospital, which in 19th century terms, meant ‘sick to death.’ She had survived her internment, but she attributed her illness entirely to the telling of stories that strictly belonged to another season than the one in which she had originally been called upon to relate to him. This was probably the first time Curtin had understood something of the indigenous rules of the road that attended story-telling – it was not a random telling, but one that belonged to a particular time or season, and that to go against that wisdom was to break the order of things, and it let in illness for that story-teller who had herself been called upon to disregard the boundary that upheld traditional knowledge.

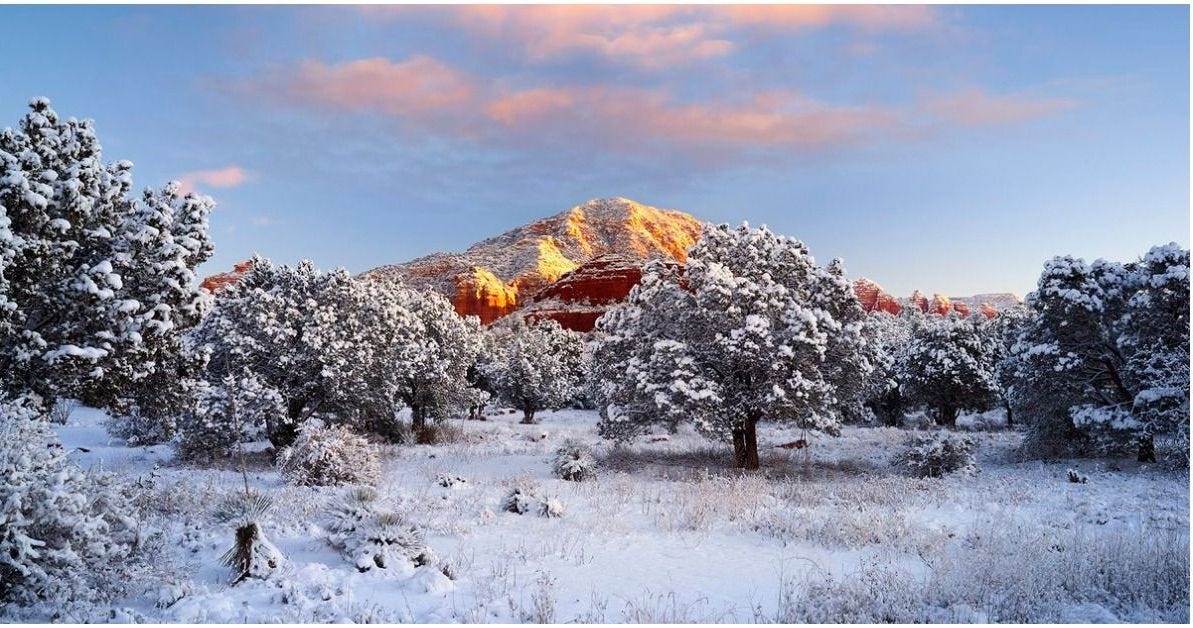

A close friend of mine discovered much the same thing when he studied at the South Western university in US, where he was studying local folklore. He was desperate to hear the winter stories of the First Nations people, but these could not be told among the pueblos unless snow lay on the ground. So there he was, seated at the dinner table of an indigenous family one day when, in the middle of dinner, snow began to fall outside. The storyteller of the family, immediately put down his knife and fork and began to tell one of the winter stories at some speed, since he himself was under constraint, unable to share these seasonal stories, until the conditions were right.

What we understand by these two matched stories is that knowledge is not knowledge that can be shared until the time is right: being within and among the conditions of a ritual event or of a sacred season along gives us the key to knowledge, for then we understand wisdom from within its context. It is not ‘just a story’ nor ‘just a ritual’ that can be randomly shared or performed at any time. Indeed, among some peoples, even a future ritual event could be stymied by speaking about it in an unguarded way.

I remember one of my own shamanic teachers who had lived among Siberian reindeer herders for half a year, during which time, he hoped to learn more about bears and the rituals about them in that latitude. He had two companions, including cameraman, with him. The problem was that the particular hunting ritual that he was keen to see and film had a specific caveat against any mention of the word ‘bear’ in the local language. This was out of respect to the bear spirit who was understood to be an ancestor to the people with whom they were staying. Several times, the cameraman spoke unguarded and openly about ‘bears.’ While the six-month sojourn during winter was not without its opportunities for learning, the bears that might have been hunted by their hosts remained stubbornly invisible – to the great frustration of my teacher, who at least fully understood how his own party had been responsible for the strange absence of bears that winter.

Being consonant with what we are trying to achieve is not just about planning, it is about spiritual respect. When we seek to open up our own daily spiritual practice, we do so from a wealth of understandings that we have already experienced, which might include, among many other things, the cardinal directions, the seasonal customs of our own land and people, our own connections with divinities and spirits that are already resonant within our soul. These are the authentic connections upon which we can build. Trying to set up a spiritual practice from odds and sodments of other people’s and other lands’ ritual life will never work: it will become what the French call ‘bricolage,’ a mere chaotic bringing together of assorted stuff that cannot speak with one voice to us.

We have to understand and learn about our own traditions, and to balance what the land shows us and what our hearts reveal to us, without either persecuting those who have other knowledge of divinity, nor of uncritically promoting our land and people to be ‘the only ones’ who know.

‘Let us, therefore, listen in the proper order to the teachings of Kairos (the appropriate time) which causes us to pause in our activities, introducing us to freedom from error, encouraging us to learn - not all things - but of the many things that we ought to learn. and which lead us to the best practices. Success lies in knowing what we must do…purification from conceit and opinion brings about success, while the presence of knowledge bring freedom. Look what will happen to you when you make your path straight: it will lead you to a most agreeable life.’ (GV XVI, 9-10)

FINDING OUR SPIRITUAL LANDSCAPE

It may surprise you to learn that, in Classical times, there was no word for ‘religion.’ Like all indigenous peoples, the Greeks saw their spiritual practice as something inherited from their ancestors, and they would speak of their ancestral customs or the traditions of their forebears. People didn’t ‘believe in’ these practices, they were just faithful or loyal to them. Anciently, in both Latin, which uses the word fides and in Greek, which uses the word pistis – the sense of these words was ‘trusting in’ or ‘loyal to’: but today, these words are most commonly translated to mean ‘belief’, which of course tries to put the ancient ancestral belonging into the corset of our modern concept of religion - something mandated that we ought to ‘believe in,’ rather than ‘keeping faith with an ancestral continuity of respect.’

It was the introduction of monotheist concepts from Judaism into Christianity that changed the whole landscape of our spiritual view in a matter of four centuries. Instead of understanding ourselves as the descendants of divine ancestors, as Aeneas or Julius Caesar, who understood themselves to be descended from the goddess, Aphrodite/Venus, we underwent a period where the ancestral divinities of a culture were, first of all seen as ‘lesser gods,’ and then, increasingly, on the margins of a world from which all other divinities had been purged, leaving just one over-arching God, who was ‘the only authentic one.’ Even though ancient philosophers spoke of the larger concept of an unformulated divinity whom they considered as the One, they also observed all divinities as adjuncts and extensions that enabled the truth, goodness and beauty of the One’s infinite variety of gifts to come into the lives of all.

As our own times destabilise, we are seeing more adherence to a fundamentalist certainty in the face of of it, at one end, and also we see a return to a more ancient and ancestral loyalty at the other; and as globalisation begins to stride over locality and national enclaves of belonging, we are seeing the rise of nationalism. Things are tending towards extremes in our time. The ability to remain loyal to the spiritual knowledge of our heart, as we pick our way through the slew and rubble of civilisations in meltdown, is a matter of trust and practice.

The Golden Verses are adaptable to anyone’s tradition, of course, and do not demand special lip-service or bowing the knee in a particular way. As our own spiritual landscape becomes clearer us, every day of our life gives us a different view of it, glimpsed through the events with which we grapple, as well as through the beauties of nature, the sharings of the heart, and the clarifying of the mind and reason. Finding our right place and time is the work of the soul. But how do we arrive at ‘a very pleasant life? Hierocles is very clear about it:

‘Now these are two excellent things; to know that we do not know, and to learn what we are ignorant of. These produce the best and most delightful life. But this delightful life is only for those who are free from opinion and replenished with knowledge; those who are not puffed up with vanity on account of anything that they know and who desire to learn what deserves to be learned.

Now nothing deserves to be learned except that knowledge which brings us to the divine likeness; which inclines us to deliberate before we act, so that we may not be guilty of any foolish actions; whatever puts us in a condition not to be deceived and misled by anyone, either by words or by actions; whatever enables us to discern the difference between the arguments which we hear; whatever makes us bear with patience the Divine Fortune and which supplies us with the means to mend it; whatever teaches us not dread death or poverty, and to practice justice; whatever makes us temperate in all our pleasures; whatever instructs us in the laws of friendship, and of the respect due to those who gave us life; and lastly, that which shows us what honour and worship we ought to offer to the Superior Beings. (GV, XV 2-3)

And with one spiral of words, Hierocles leads us right back to our beginnings, and the respect that paves the first steps of these Golden Verses, lest we forget that these are the primary road to virtue, to spiritual authenticity, and to our belonging to the wider cosmos. Whether we know or do not know, if we are encompassed by the understanding and care of those who share the road with us – with friends, relatives ancestors, daimons, the oath, the gods and the immortal ones - we find we are held firm in the divine embrace.

§ CONSIDER §

* Consider what happens in you when someone knows something more perfectly, from experience, or from a place of true understanding, than your own view. How much opinionated arrogance do you have to deal with?

*From a position of unknowing, consider your ancestry and lineage stretching behind you. To what do you feel you are still loyal, what is the trust that you know within that your ancestors would also recognize as precious? How does that guide you? Where does it lead you into prejudice and judgement? How does it open the way before you and those descendants who follow you?

*Where in your life is the spiritual respect that enables all beings to be a part of the cosmos as equally precious? What best sustains and encourages those seeking their spiritual way?

*Where is the divine likeness in your life? How do you reflect that likeness to all you encounter?

MEDITATION

‘Learning what we need to know’ is the work of a lifetime. Some part of that knowing is our upbringing, and our formal education, and a lot of it is about life. Here, Iamblichus speaks of the ideal training of those who imbibe philosophy, and how Pythagoras intended his students to learn. The mixing up of philosophy with other matters, especially when taught by the Sophists who were the spin-doctors of their day, easy with words but also anyone’s to hire, was especially injurious to his students.

The way that we inculcate knowledge in others and how we learn ourselves is especially important, for if they are mixed together we have difficulty in establishing what is true and what lies unknown. We can see how some part of this verse was upheld by Pythagoras’ followers in that they did not call him by his personal name, but rather as antos or ‘himself.’ Also, he was everywhere acclaimed as one of the wisest of men, with many seeing him as ‘an earth-dwelling daimon’ while he was alive, or as the exemplar of Apollo, and hence the use of the respectful ‘himself.’

‘Just as dyers, while cleaning garments, treat what is to be dyed with a mordant, in order that the dye be indelible in that which absorbs it, and never fades, so the divine man (Pythagoras) prepared the souls of those in love with philosophy in order that he not be mistaken about anyone who we hoped to be among those noble and good. For he did not traffic in fraudulent doctrines or snares with which so many Sophists, who never devote themselves to anything good, entrap young people, and he had a knowledge of things divine and human. But these Sophists, having made this (Pythagoras’) own teaching a pretext for doing many dreadful things, catch the youth as in a net, neither in orderly fashion, nor by chance. Accordingly, they make their hearers undisciplined and heedless. For the pour theories and divine discourses all mixed up into characters agitated and disturbed, just as if someone were to poor clean and clear water into a deep well full of mud, for such a one both stirs up the mud, and also spoils the water.

The same then, is the method of those teaching, and being taught in this way. For dense and bushy thickets grow about the wits and hearts of those not purely initiated in the sciences, overshadowing all the civilised, gentle, and rational in the soul, and hindering the intellectual part from clearly increasing and emerging. ..Such indispensable attention as this Pythagoras believed must be given to students prior to philosophy, and he ordered that both exceptional value and most exact investigations be given to the teaching and communication of his doctrines. And he examined and judged the conceptions of candidates with every sort of teaching, and array of scientific theory.’

Iamblichus: The Pythagorean Life 17, 76-77, 79)

Please join me as I introduce Pippa Bondy at Hawkwood College next month.

22-24 August 2025 THE WAY OF COUNCIL: with Pippa Bondy,

This ancient practice of sitting in a circle and speaking and listening from the heart is our innate birth-right. In modern times the core practice of Council sets a container for empathy and honesty. It provides a way of bearing witness and accepts diversity in our self and each other and helps cultivate non-hierarchical power. When in Council we step into a timeless space and the creative source flows through us. Through the medium of The Way of Council we will embrace the spirit of enquiry; meaning to open a space of ‘not knowing’ - allowing a state of creativity, a field of fresh new energy and awareness that onnects us to a deeper wisdom within. The practice of Council deepens and enhances communication anywhere that dialogue takes place, be it the home, work-place or wider community, offering an effective means of resolving conflicts, making decisions in a group framework and discovering the deeper, often unexpressed needs of individuals and organizations. Council has been used and is effective in many different settings from health care, schools, businesses and community groups.

Pippa Bondy is a wilderness rites of passage guide and a carrier/trainer of Council. She will lead us to experience the empty vessel that Council provides to look at truth, intentions, questions, fixed ideas, mistakes, and other issues in ways that will help support ourselves, our shamanic clients, our community and the world. Fees: Single £495, Shared £445, Non-res £345.) Please send your non-returnable deposit of £150 payable to Hawkwood College, Painswick Old Rd., Stroud, Glos GL6 7QW (01453 759034)

True wisdom appropriate for these times, this article has been really useful.