GOLDEN VERSES: STEP 31

FREEING THE SOUL

The remedial action of philosophy upon the soul is the healing that we each seek. In this post, we consider how the soul is in prison and how it is freed. The promise of Pythagoras continues to sustain our study, if we engage with the Golden Verses as we have been shown.

§ Sacred nature reveals and shows to us the most hidden mysteries.

If she imparts her secrets to you,

You will easily master all the things which I have shown you.

And by the healing of your soul, you will free it from all suffering. §

Verses 65-67

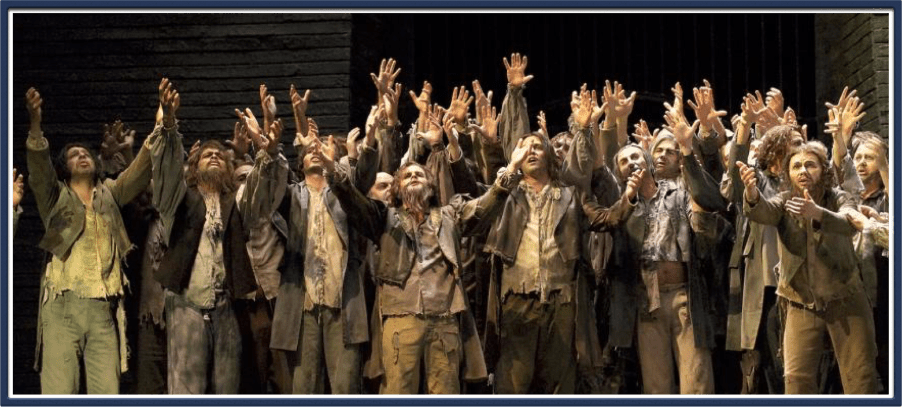

GAINING THE CAP OF FREEDOM

In the Roman Empire, anyone could become a slave: even your parents could sell you into slavery if they couldn’t support themselves any longer. But generally any captive of Rome’s many wars, both soldier or civilian, male or female, old or young, could end up enslaved. Those with a skill or education came off better, as they were slaves to whom some respect had to be shown, but unskilled people did not fare so well. Slaves had no personhood at all: they were just a piece of property with no free will. They had no recourse to good treatment or health care, beyond that which a considerate owner might provide: most slave owners wanted to get more work out of a slave, and so they generally determined, to the mouthful, what kind of food would sustain the level of work in which they were engaged. Spinning women had a different kind of food allowance than a more physically active male slave, for example. Their feelings or thoughts were of no consequence to their owners: there were no slave unions nor beneficent organisations governing their welfare – a thought which is unspeakably abhorrent to us today.

Of course, there were slave owners who did free their slaves, for good service or out of respect of the love that was between master and slave. The master brought his slave before the magistrate and stated the grounds the intended manumission. “The lictor of the magistratus laid a rod on the head of the slave, accompanied with certain formal words, in which he declared that he was a free man. The master in the meantime held the slave, and after he had pronounced the words ‘I wish this slave to be freed,’ he turned him round and let him go. The magistrate then declared him to be a libertus or liberta – a free person. Freed men were given the soft, felted pileus cap, which we now know as the Cap of Freedom, from its usage during the French Revolution.

Epictetus speaks about how the Cynic philosopher, Diogenes (421-323 BCE) was taken captive by pirates, and sold into slavery in Corinth, into the house of Xeneides who, having assessed his slave’s knowledge, appointed him to be the tutor of his children, because he liked Diogenes’ spirit:

‘This is how freedom is acquired, as Diogenes used to say, “Ever since Antisthenes made me free, I have not been a slave.” How did Antisthenes make him free? Hear what he says: “Antisthenes taught me what is my own, and what is not my own; possessions are not my own, nor kinsmen, servants, friends, nor reputation, nor places familiar, nor any mode of life; all these belong to others.” What is your own? “The proper use of impressions.” This he showed to me, that I possess that ability free from all hindrance and compulsion, for no-one can put an obstacle in my way, no-one can force me to deal impressions otherwise than I wish. Who then has any power over me? Philip or Alexander, or Perdiccas, or the great king of Persia? How have they this power? For if a person is fated to be overpowered by anyone, then long before that they must have been overpowered by things. If pleasure is not able to subdue us, nor pain, nor fame, nor wealth, but we are able, when we choose, to spit our poor entire body into some tyrant’s face and depart from life, then whose slave can we be? To whom can we still be subject?” (ED 3:24, 67-71)

Now, in case you are confused, this Antisthenes (446-366 BCE) was a pupil of Socrates, but he was not the rescuer of Diogenes from his Corinthian slavery, as you might infer from this, but rather the philosopher who originally taught Diogenes the ascetic principles that came to be central to the Cynic philosophy that he lived out. Like many of the mendicant ascetics of the East, Diogenes owned nothing, lived on the streets in a pithos or huge jar, begged his food, and used his rustic simplicity to criticise the social values of his time. Being owned as a slave did not enslave Diogenes: he was already free in his own estimation.

While we feel subjected, we cannot be free. What is subjects us? Epictetus, the philosopher who had once been a slave himself considers, what can master us and where we are really free:

“Have we so many masters, then?” We have many. For, prior to all human masters, we have circumstances themselves for our masters. Now they are many; and it is through these that the those who control the things inevitably become our masters too. For no one fears Caesar himself; but rather death, banishment, confiscation, prison, disgrace. Nor does anyone really love Caesar unless he be a person of great worth; but we love the riches, the posts of tribune, the praetor, the consul. When we love, hate or fear such things as these, whoever has the disposal of them must necessarily be our masters. We come to worship such masters as gods. For we consider that whoever has the disposal of the greatest advantages is a deity; and then further reason falsely, “Whoever has the power to confer such benefits must be a god.” For if we reason falsely, the final inference must be also false.’ (ED 4;1, 59-61. )

As part of the healing of our souls, the cure has to be sought in other kinds of terms. When we begin enter into the full dignity of our sacred being, when we know our soul, we awaken into another condition. In Plato’s Meno, the discussion follows the theme of former lives and what we remember: here, Plato quotes Pindar again, the exact same passage which we already read in the last step. He considers why certain people take up a sacred profession:

‘Some of them were priests and priestesses, who had studied how they might be able to give a reason for their profession. There have been poets, also, who spoke of these things by inspiration, like Pindar, and many others who were inspired. They say that the soul of man is immortal; so, when it comes to that end which is called “dying,” but at another time it is “born again,” but it is never destroyed. Therefore, we ought to keep ourselves as pure as we can. “Persephone exacts the penalty of the ancient world, in the ninth year she gives up their souls again to the sunlight in this world above. From these come noble princes and people swift and strength, and of the highest wisdom; and, for all time to come, people call these pure heroes.” Since, then, the soul is immortal and has been born many times, since it is seen all things, both in this world and the other, there has knowledge of it all. No wonder, then, that the soul is able to recall to mind goodness, and all these things, for it knew them beforehand. For, as the soul has learned all things, there is nothing to prevent anyone who has recalled – or, as people say, “learnt” – only one thing from discovering all the rest for themself, if they will pursue the search with resolution. For, in the end, all learning is nothing but recollection.’ Plato Meno.

It is this very recollection that brings us our freedom.

BEAUTY

Beauty has ever been the sign that goes before us like a beacon. Whatever is beautiful and whole with goodness lifts us completely out of the contention of life’s sufferings because it is reminder of the transcendence of sacred wholeness. It does not change and remains a guide. But in a world where aesthetic beauty everywhere is being over-turned by purposeful degredation, or by counter-cultural values that appeal to the margins of society, it is often seen as being ‘out of touch’ if you don’t bow the knee to the cult of the degredation of beauty. Heirocles tells us our blindness and deafness to the mysteries that lie before us, is our ‘pernicious contention’ or innate strife that we looked at in step 29.

‘Instead of increasing and suffering it to grow, we ought to avoid it by yielding, to learn to deliver ourselves from our evils, and to find out the way to return to the divine. For by this means, the light of God and our own light, concurring together, work to complete and perfect t this manner of showing so that it ensures the liberty of the soul, it deliverance from all the miseries in the world, a lively taste of divine goodness, and the recalling of the soul from banishment into its true country.’ (GV. XXXV, 17-18)

The verses of this step tell us that is by Sacred Nature that the mysteries are conveyed to us. And this is true of the beauty within our everyday world as much as the instinct to beauty that is hard-wired in our souls. We each innately understand beauty, however simply that shows itself: the first snowdrops emerging from the icy winter, the glint of sunlight upon still water, the busy birds that fly and sing, the joyful grace of animals, the play of children, - all these have beauty in our sight.

Philosophically speaking, that which is simplest and most true, that which shows itself to our souls is revealed as beautiful, bringing us once again into recollection of our own truth and beauty in the light of the sacred. Freedom for the soul is the freedom to be guided by beauty, for it kindles love in our deepest core.

What we have been given by Sacred Nature is here added to the promise of Pythagoras that, by our continuing practice of daily observing how we did each night, and by our performance of step 23: we will come to master his precepts and come to the healing of our souls:

‘Practice these teachings with all your might,

Meditate upon them attentively,

Love them ardently with all your heart,

For it is these will set your steps on the path of divine virtue.’

The poem below is by Joachim du Bellay, the early 16th century French humanist poet and founder of Les Pleiades: he and his group enabled people to gain acquaintance with the wisdom of the Classical which had started to flood into the European West, after the fall of the Byzantium empire in 1453, as scholars and books fled to safety. Texts in Ancient Greek, previously unknown in the West, came as a revelation, thanks to the translations of people like Marsilio Ficino. It is staggering to consider that the only text of Plato’s available to the medieval world had been the Timaeas. This sudden access to the wisdom of the past brought a breath of fresh air and an alternative vision to a world corseted in the narrow dogmas of a belief, one that had outlawed any thought of reincarnation, or the ability to follow the path of self-knowledge. It revealed the outline of a philosophical freedom that could take flight upon the wings of love and beauty.

If our life is less than a single day

In eternity, and the year in its turn

Wastes our days, without hope of return,

If everything is born to decay,

Why my captive soul your dreams display?

Why for the shadow of our day so burn,

If for flight to a clearer one you yearn,

Graced with wings to help you on your way?

There, is the good, every soul’s desire.

There, the rest to which all men aspire,

There, is the love, there the delight in store.

There, O my soul, in highest heaven clear,

There you may realise the Idea

Of the beauty, that in this world I adore. (Joachim Du Bellay)

§ CONSIDER §

*** How does Sacred Nature reveal itself to you? What mysteries have bloomed in your soul?

*** What best reduces or cancels the sufferings that you suffer?

*** What is it about being human that encourages you to take heart in your divine nature?

MEDITATION

The two passages from Iamblichus below look deeply at the power of philosophy to free the soul by acknowledging that we have to first free our minds from constricting beliefs. By pursuing the way of the Gods, by entering deeply into the mysteries, the way grows clearer to us, until our communion with the sacred is perfected. In the second passage, Iamblichus reminds us that the way of theurgy – literally, ‘god-work’ – is a sovereign method of maintaining our communion with the sacred. Seeking beauty through prayer, as well as by deeds; opening our souls to whatever mysteries, invocations, and spiritual practices that will lead us deeper into this terrain, is the sure road to a recollection of our sacred nature.

‘The greatest teaching of all, in regard to courage, is setting before yourself this principal aim: to rescue and free the intellect, subdued from infancy from so many imprisonments and constrictions. Without the intellect, no one would thoroughly learn anything sound or absolutely true, nor would you perceive through which sense organ you were functioning. For the intellect sees and hears all, but all other things are deaf and blind. The second greatest teaching is when the intellect has been purified and in various ways made fit for taking initiation into sacred rites, in order to clothe the intellect and give in some share of beneficial and divine teachings, so that it neither greatly fears removal from the body, nor when it is led to things incorporeal, it does need to turn away its eyes, because of the brilliant splendour, nor turn back to those emotions that nail and fasten the soul to the body. In short, that the intellect become unconquered by emotions concerned with earthly life and which debases the soul. For the training and descent through all these matters was the practice of perfect courage.’

Iamblichus: The Pythagorean Life 32, 228

‘Hence, we must consider how one might be liberated and set free from these bonds. There is, indeed, no way other than the knowledge of the gods. For understanding the Good is the paradigm of well-being, just as obliviousness to the Good and deception concerning evil constitute the paradigm of evil things ... But the sacred and theurgic gift of well-being is called the gateway to the creator of all things, or the place or courtyard of the good ... it prepares the mind for the participation in and vision of the Good, and for a release from everything which opposes it; and, at the last, for a union with the gods who are the givers of all things good.’ Iambichus DM 10.5(290.12–291.1;291.10–12;292.1–3).Cf.also1.7(21.2–9)

We have just four more steps left in our studies.