GOLDEN VERSES: STEP 32

What Nourishes and Purifies Our Life

In this step we return to one of the basic teachings of Pythagoras, one which has connections to both body and soul, and to our wider reincarnational lives.

§With due discernment, avoid the foods which are discussed

In the books, Purifications and Release of the Soul. §

Verses 68-69

DIET AND DUTY

This verse refers to two treatises that Pythagoras had created for his followers: but On Purification and On The Release of the Soul, have not survived. We know from some fragmentary mentions that they outlined how a Pythagorean student might live in harmony with the universe. It might seem odd to have this verse so deeply embedded in the second half of the sequence of the Golden Verses that are dedicated to the purification and preparation of the soul. While today not everyone can always see the connection between our physical diet and our spiritual dedication, that connection between the two was prominent in parts of the ancient world.

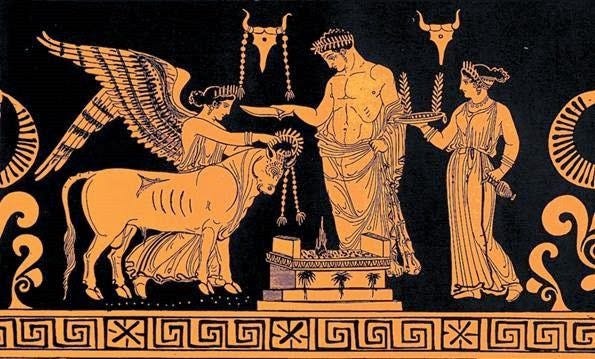

To fully understand step 32, we need to look at its ancient Greek context, where living in one of the city states meant that its annual, seasonal, and civic rites involved obligatory participation. This most often entailed animal sacrifices. As still happens in indigenous cultures in parts of the world today, it was expected of everyone to both witness these rituals, in which parts of the animal were offered to the Gods, and also required to participate in eating the remaining animal parts in a socially-determined act of piety. In most traditional communities today, the slaughtering of an animal works in much the same way – part of the animal is offered to the divine, and then the meat is shared among the community. It is sacrament and feast all at once.

The sacrifice of animals was part of many aspects of ancient Greek life.Hecatombs were large-scale sacrifices to the gods, where the offering of many animals was commonly part of public religious festivals in ancient Greece. Kheiliaswas a term for offerings made to the dead, which included libations poured on graves as a sign of respect and remembrance. Thysia was a type of sacrifice where animals were offered to the gods, often accompanied by libations as part of the ritual. We can readily see how, when Christianity was established as a state religion, that the symbolism surrounding Christ as the offering sacrifice had such a prominent emphasis in its liturgy. Of course, the Jewish tradition also used animal sacrifices, as we see from temple practice.

In antiquity, those who fully committed completely to the Pythagorean life were expected to be strictly vegetarian. But this was not a recognised or normal thing in ancient Greece, where vegetarianism was seen as not only as very eccentric, but as a subversive act of great impiety towards the state cult of the gods. Pythagoreans and Orphic practitioners alike espoused strict vegetarianism, and were both roundly mocked and censured for their refusal to partake in the sacrifices at state rituals. Pythagoras himself ate simple and often uncooked foods, never eating meat or drinking wine. However, there are accounts of him breaking this rule within the context of group or state rituals, so we cannot be strictly definitive about his views.

Pythagoras was known for worshipping the gods before ‘bloodless altars,’ according to Hierocles. His followers fell into two camps: those who held to a strict regime and those who did their best to follow the main precepts, but who partook of the state ritual sacrifices like other Greeks. But Pythagoreans also attended temples and sacred rites, and everyone was instructed to behave themselves in a manner that did honour to the gods, without dishonouring their principles:

‘To the women himself (Pythagoras) talked first about sacrifice, just as they would with someone else about to make prayers on their behalf, to be good and noble… They were to make what they intended to offer to the gods with their own hands, and to offer them at the altars without the need of slaves to assist them. Round cakes, cakes of ground barley, honeycombs and incense. They were not to honour the divine with slaughter and death nor to indulge in great expenditure at one time, as if they were never going to approach the altars again.’ (Iamblichus: The Pythagorean Life 11, 54)

The most dedicated Pythagorean students lived in community and were known as the mathematici or ‘mathematicians’ (from the Greek mathema or ‘the art of learning knowledge’.) We understand ‘mathematicians’ in narrower way today - although these students did learn the secrets of mathematics also. This title was used only of those students were immersed in the contemplative study and practice of philosophy, and who had undergone a very long inculcation; they had signed up to the whole Pythagorean formation, including a strict vegetarian diet.

There were also students who practiced as best they could but who had public duties and lived in ordinary society; while they were they could not keep so a strict a regime; these were known as acusmatici or ‘listeners,’ because they could only hear Pythagoras speak from behind a curtain. They could not commit fully to that complete way of life, but they met together to encourage each other, much as we are doing here.

What feeds our body needs to be in accordance with what nurtures the soul. If we feed on the results of cruelty and abuse, Pythagoras tells us, our soul is soiled. Iamblichus writes ‘there is a congenial partnership of living beings, since, through sharing life and the same elements and the mixture arising from these, they are yoked together with us by brotherhood.’ (Iamblicus VP p. 108) While Plutarch tells us that because there is one spirit penetrating the entire cosmos like a soul, it also unites us with the animals. He reasons that if we kill and feed on them, we will be destroying our kindred.

(You can read more of this text here: https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Moralia/De_esu_carnium*/1.html#:~:text=Even%20when%20it%20is%20lifeless,what%20is%20foreign%20to%20it.)

Of course, to put these teachings into another context, Greece is part of the fertile Mediterranean where many kinds of foodstuffs are and were easily available, but in parts of the world that have no arable possibilities, like the Arctic Circle, to be vegetarian is not an easy or sustainable option. Spiritual and ethical ways arise within the context of their place.

‘All things that come to be alive must be considered akin’ is the understanding of the Pythagoreans. (Porphyry, Vita Pythagoras 9DK 14, 8a) This arises out of the doctrine of reincarnation where the same soul incarnated as an animal in one life can reappear as a human being in a following life. Not eating those who might once have been your mother or brother in a previous life was a very real consideration among Pythagoreans, as it still is today for Buddhists.

Porphyry, who was the commentator of Plotinus and the teacher of Iamblichus led a completely vegetarian life and left us a complete treatise on why it might be necessary: Abstinence from Animal Flesh, translated by Thomas Taylor, can be read here: https://www.platonic-philosophy.org/files/Porphyry%20-%20On%20the%20Abstinence%20of%20Eating%20Animals.pdf

In this work, he wrote; ‘Abstinence from animayr creatures was a major contribution to the blessed life of the most ancient people. For that reason, there was no war: aggression towards each other came in later, at the same time as injustice to animals.”

Likewise, Empedocles, who lived just shortly after Pythagoras, followed his vegetarian principles, as we can see from his poem Purifications. Here he is speaking of the falling off from the Golden Age and its descent into the successive ages: it starts with people and animals being held in equal respect, and moves into the killing of animals for food. He is not speaking here in the 2nd stanza of human beings, but of humans taking their animal relatives for sacrifice – something that Pythagoreans would not partake in. In the 3rd stanza he speaks of those humans who have been in other forms.

‘Will ye not cease from this great din of slaughter?

Will ye not see, unthinking as ye are,

The father lifteth for the stroke of death

His own dear son within a changed form,

And slits his throat for sacrifice with prayers

A blinded fool! But the poor victims prays,

Imploring their destroyers. Yet not one

But still is deaf to piteous moan and wail.

Each slits the throat and in his halls prepares

A horrible repast. Thus too the son

Seizes the father, children the mother seize,

And reave of life and death their own dear flesh.

Ah woe is me that never a pitiless day

Destroyed me long ago, ere yet my lips

Did meditate this feeding’s monstrous crime!

Drawing the soul as water with the bronze…..

Withhold your hands from the leaves of Phoebus’ tree …

Ye wretched, O ye altogether wretched,

Your hands from beans withhold! ‘

(Empedocles The Purifications, 136-141)

Above, ‘drawing the soul as water with the bronze’ is referring to the brazen knife that slit the throats of animal sacrifices. The ‘leaves of Phoebus’ tree are the laurel leaves with which the victors at the games or rulers wore to denote their victory: this is a way of saying ‘don’t seek honours.’ While of course, the final instruction is one we met near the beginning of this course, the Pythagorean prohibition from eating beans.

Whatever your own choices or diet, we all agree that our food should not be sourced from cruelty to animals, and throughout the world we now have options that enable us to eat very well from many sources. I myself was a vegetarian by choice for the first 34 years of my life, but my body needed more support when I conceived my son, and though my diet has changed, I still eat meat or fish very sparingly. According to a study of last few UK census results, it was predicted that a quarter of all Britons will be vegetarian by the end of last year. Only the next 2031 census will reveal that figure is borne out.

I have recently been re-reading Hugh Walpole’s great family saga, The Herries Chronicle. The middle book, Judith Herries, has a character who is made aware of how vulnerable/culpable we all are, after witnessing a bear-baiting where he tries to defend the bear, at some cost to his own safety, when everyone else present wants to taunt and injure it. His aunt, Judith, herself comes to realise that, ‘Until the bear is made safe, nothing in the world will ever be safe.’ This is such a Pythagorean response to cruelty to animals, as well as underscoring that, if we can do these things to animals, we will most likely do them to human beings also, if we follow our basest nature. Peace in the world is unlikely, ‘until the bear is made safe,’ as Pythagoras himself observed, according to Iamblichus:

‘And he ordered abstinence from living beings for many other reasons, but mainly because the practice tended to promote peace. For once human beings became accustomed to loath the slaughter of animals as lawless and contrary to nature, they would no longer make war, thinking it even more unlawful to kill a human being. War is the leader and lawgiver of slaughters; for by the these it is provided with sustenance. The injunction “not to step over the beam of a balance” is also an exhortation to justice, ordering the practice of all things just… It is apparent then, through all these things that Pythagoras took great pains about the practice and teaching of justice to human beings both in his deeds and sayings. (Iamblichus VP 186.)

Since the instruction in this step about diet and purification comes at the penultimate point of the Golden Verses, we are forced to consider what it is we take not only into our bodies, but also into our souls and minds.

PURIFICATIONS

To partake in any of the mystery cults of the ancient world, it was normal first of all to be purified. At the Eleusinian Mysteries, candidates were brought into the Lesser Mysteries by fasting, by immersion in the sea etc.

Even if individuals were just going to the temple to worship, they prepared themselves. At the temple, guardians were positioned near the entrance to refused entry to anyone who was not in a fit state to enter: this would include those who were unclean in person or dress, or not fit to enter because they were unwell, or mentally deranged, or whose behaviour was disruptive. As Epictetus says, ‘Would you accompany us even into the temples in such a state, where it is forbidden to spit or blow your nose, you are nothing but spittle and snot?’ (ED 4:11,32.) To approach a temple in a poor state of preparation was perceived as disrespectful to the gods. There is little difference between our own times and the Classical Age: being suitably dressed, acting in a respectful manner, and not approaching the rites without prayer and preparation are still the criteria of in churches, temples and shrines the world over. Nothing has changed there, only our own reactive or rebellious attitudes about places of worship.

Iamblichus wrote of those who learn philosophy, that we cannot, ‘pour teachings and divine insights into individuals confused about ethical standards and troubled by obsessions. This would be like someone pouring pure, clean water into a deep well full of mud. Such a person stirs up the mud as well as getting splashed by it, spoiling the clean water. (Iamb. VP 77)

Epictetus also says, ‘Whatever attention to purity that we suppose to be a human attribute, know that we first received it from the gods themselves. Since the gods are by nature pure and undefiled, the closer that we approach them through our reason, the more we are attracted to purity and cleanliness. But since it is impossible that human nature can be entirely pure, composed as we are, it is reasonable to suppose that our essence strives to be as pure as possible.

The first and highest purity or impurity, then, is that which is manifested in the mind. But you will not find the impurity of the mind and body to be alike. For what stain can you find in the mind, unless it is something which renders it impure in its operations? Now, the functions of the mind are its motivations to act or not to act; its desires, aversions, preparations, intentions, assents. What, then, is that which renders the mind defiled and impure in these functions? Nothing else than its perverse judgments. So that the impurity of the mind consists in bad judgements, and its purification in forming correct judgements. A pure mind is one that has right judgements, for these alone are unmixed and undefiled. (ED 4:11, 5-8.)

The Pythagoreans did not usually publish their teachings for the general public, although it is clear that such books were in circulation among their own followers. The deeper teachings were conveyed in person, and also came together from personal revelation, which is a how the Mysteries were conveyed in antiquity and still today – no amount of reading or instruction will bring us to the brink of the Mysteries: they arise in us, similar to the way that Clement of Alexandria speaks of them here:

‘Objects, visible through a veil, look greater and more imposing than they are in reality; as fruits seen through water, and figures behind the curtain, which are enhanced by added reflection to them ... Since the thing expressed in a veiled form allows several meanings simultaneously, the inexperienced and uneducated person fails, but the Gnostic apprehends. Now it is not wished that all things be exposed indiscriminately to everybody, “or the benefit of wisdom communicated to those who have their soul in no way purified, for it is not just to give to any random person things acquired with diligence after so many labours or to divulge to the profane the mysteries of the word”. They say that Hipparchus the Pythagorean was expelled from the school, on the ground that he had published the Pythagorean theories, and a mound was erected for him as if he had already been dead. In the same way in the barbarian philosophy, they call those “dead” who have fallen away from the teaching and have placed the mind in subjection to the passions of the soul.’ (Clement of Alexandria Strom. V 56, 5–57, 4)

The ability to be aware of our place on earth is encompassed by this verse. And there is a deep practical application that is required of us. This practicality is something that, even in the ancient world, some practitioners lacked or failed to pay attention to. Iamblichus tells a story about Thales who went around with his head in the air:

‘it is said that Thales, while astronomizing, and looking intently upward, fell into a well, and a bright and lively Thracian girl taunted him about the accident, saying that in his eagerness to know what was in heaven he could not see what was around him and under his feet. Now the same taunt is good for all students of philosophy. They are indeed ignorant of what the nearest neighbour is about, and almost whether or not he is a human being.’ (Algis Uždavinis, Philosophy as a Rite of Rebirth, p.64)

Our philosophy has be something of the body, as well as of the soul, otherwise it has no application. While we no longer have the two books that Pythagoras wrote, we appreciate that the physical diet, the discipline of the mind through meditation, and the purification of the soul through the nightly examination of our day’s deeds, all come together here. The civic virtues of behaving in a self-aware and considerate manner, the contemplative striving after virtue, the purification of the soul through rites that are theurgic are the three stepping stones to being a fully-operative human being.

Hierocles sees these three steps in terms of a body, with the foot representing the civic virtues which have formed the foundation of this course; with the hand as the contemplative and companionable way of progressing with the help of our daimon; and with the eye as the Nous of the creative intelligence that the soul brings to bear upon our whole life.

§ CONSIDER §

*** What is it that you are taking in your body that takes you from perfect harmony with the sacred beauty of the Cosmos? What are your taking into your mind and soul that is neither informing it nor sustaining it in good balance?

*** What procedures do you follow to purify your body, being, mind and soul? What do you need less of to be healthy, truthful, wise? What do you need to moderate more carefully. What puts you, your system and your soul over the edge?

** Porphyry writes about the passions which seize upon us: ‘when recollections, imaginations, and opinions are collected together, they excite a swarm of passions, such as fear, desire, anger, love, lasciviousness, pain, worry, and disease, and cause the soul to be full of similar perturbations. To be purified from all these is most difficult, and requires a great contest, and we must bestow much labour both by night and by day to be liberated from an attention to them, and this, because we are necessarily complicated with sense.’ With regard to all these things, look closely at your nightly examination of your day, from Step 22.

MEDITATION

The following passage from Plotinus Enneads, uses the image of a group of dancers who sing as they dance. This sustained metaphor works well in the Greek imagination, because social circle dancing was something that everyone understood: people come together in a ring, singing and dancing as one at parties, gatherings as well as being part of ritual assemblies and play-going. Such dances always had a chorus leader who set the tone and pitch, and helped to coordinate the dance, so that all were harmonious together.

‘We perpetually revolve around the divine but we do not always behold it. As a circle of choral singers, though they move about the chorus leader in their dance, may become diverted by something other than the choir, and so become discordant, so also when they convert themselves again to him, they sing well, and truly subsist about him – so too we perpetually revolve about the principle of all things, when we are perfectly detached from it, and no longer have any knowledge of it. Nor do we always look to it; but when we behold it, then we obtain the end of our wishes, and rest from our search after felicity. Then also we are no longer discordant, but form a truly divine dance about it.

In this dance, however, the soul beholds the fountain of life, the fountain of intellect, the principle of being, the cause of good, and the root of soul. And these are not poured forth from this fountain, so as to produce any lessening…’ Those things remain whole and entire….’ Just as if the sun, being permanent, light also should be permanent, light should be permanent. For we are not cut off from this fountain, nor are we separated from it, … but we are animated and preserved by an infusion from thence, this principle not imparting, and afterwards withdrawing itself from us; since it always supplies us with being, and always will as long as it continues to be that which it is. And we are what we are by verging to it.’ (Plotinus.Enneads. VI.9.8.39–46)

Just two more steps remain of our course.

14-15 February 2026 The Glastonbury Occult Conference is nigh! You have time to have celebrated Imbolc or Lupercalia, so you have no excuse! With a wealth of great speakers and workshops, how can you resist? It is time to start excitedly running towards the booking office to secure your place. John and I will both be speaking on the Saturday morning - an event so momentous, we have quite astounded ourselves. We will be speaking the the Art of Evocation and The Appearances of the Green Man. It is also the occasion of our 51st Anniversary of being together, so please come! Booking in link. Still some tickets left, if you are quick!

https://www.occult-conference.co.uk/?fbclid=IwY2xjawPq7-lleHRuA2FlbQIxMQBzcnRjBmFwcF9pZBAyMjIwMzkxNzg4MjAwODkyAAEeN87sBgtCyXL3kxDI5nxieiMK6RjRdbmq-yI27mRpGwuolra7txfzhElcziE_aem_kLQSTAYnexvftXl081PSTQ