In the last step we read how mortals were composed of the left-over remnants of the Titans and of the essence of Zagreus/Dionysus, according to the Orphic myth, while in Plato’s Timaeas, we were mixed in the krater or mixing bowl in which the Demiurge had made the stars and planets. So, we are all made up of both star-stuff but also rubble of the titanic rebels who fought against the gods. In Part 2 we attempt to bringing ourselves into order, with the help of the four Cardinal Virtues which are the governing principles of a balanced human life.

PART 2: INTRODUCING THE CARDINAL VIRTUES

Having begun with the steps that lead us into right relationship with the inhabitants of the ensouled cosmos, Hierocles now paves the way by giving us the practical steps that enable a human being to begin walking this path of The Golden Verses. He is concerned with our foundational ability to conduct ourselves by the wider wisdom available to us, which is why we hear first about the cardinal virtues: Temperance, Fortitude, Wisdom, and Justice. The cardinal virtues appear in Plato’s First Alcibiades, where they are held up as something so essential to human life that the King of Persia’s son was carefully imbued with these virtues by specially-chosen tutors who excelled in the cardinal virtues:

‘These are chosen from such as are deemed the most excellent of the Persians, men of mature age, four in number; ones who each excel in wisdom, justice, temperance, and fortitude. By the first of these tutors they are taught the magic of Zoroaster, the son of Oromazes, by which magic is meant the worship of the gods; and the same person instruct them likewise in the art of government.

He who excels in the science of justice teaches them to follow truth and every part of their conduct throughout life. The person who excels in temperance teaches the young prince how not be governed by sensual pleasure of any kind, that he may acquire the habits of a free man, and of a real king, by governing first all his own appetite instead of being their slave. And the fourth, he who excels in fortitude forms his royal pupil to be fearless and intrepid; so that his mind, under the power of fear, might not be that of a slave.’ (Plato: The First Alcibiades,121e-122a)

Now, the Persians were the enemies of the Greeks, but despite their hostility towards what Greeks saw as an alien culture, they nonetheless extolled the Persian antecedents which led back to ancient Mesopotamian wisdom: indeed, Pythagoras thought so well of their wisdom that he himself sought initiation in the Babylonian mysteries – sometimes also called the Chaldean wisdom. The veneration of this elder tradition continued right through the history of Neo-Platonism.

Education doesn’t concern itself with virtue so much these days, preferring to trade in either morality or ethics, while still offering little help on practicing either of these things. The Golden Verses present us with the essential entry point, leading from the bottom rung of the ladder to a series of virtues. Let us just recap what they are again:

Verses 1-23 or Parts 1-6 teach civic philosophy, or a dedication to the common welfare of society. By attending to our responsibilities for our behaviour, we find a better way of interacting with those around us.

Verses 24-30 or Parts 7-8 teach contemplative philosophy, or the point at which theory truly becomes practice, and where the practice itself illuminates theory, making it alive. This is usually accompanied by meditation and observation, helping our consciousness to be both watchful and engaged with the teachings.

Verses 31-34 or Part 9 teach telestic philosophy, or the practice by which what we have learned reveals what is god-like, and where the soul realizes its divine likeness. ‘Telestic’ means ‘that which purifies the soul.’

Porphyry reminds us that the exemplary or paradigmatic Cardinal Virtues are what crown and coordinate the lesser virtues: ‘The object of the civic virtues is to moderate our passions so us to confirm our conduct to the laws of human nature. That of the purificatory virtues is to detach the soul completely from the passions. That of the contemplative virtues is to apply the soul to intellectual operations, even to the extent of no longer having to think of the need of freeing oneself from the passions… The practical virtues make man virtuous; the purificatory virtues make us divine or make of the good man a protecting deity; the contemplative virtues deify; while the exemplary (Cardinal) virtues make a man the parent of divinities.’ (Porphyry: Launching Points of the Soul. p1, 4.)

To modern ears, ‘being virtuous’ sounds like an invitation to become a sour-mouthed puritan goody-goody who is likely to be avoided by everyone. In Greek terms, a virtue was arete or ‘an excellence.’ it meant being vigorous with life, courageous in battle, just and wise in our daily life: this meant only in your integrity, but in every situation.

We could say that the promising bloom which is upon every human being only becomes fruitful if we have the virtues to ripen us.

Epictetus outlined a three-part programme for anyone in training to be virtuous and good, which is very helpful to our own study and practical implementation.

1. Mastering the passions and desires: ‘which bring about disturbances, confusions, misfortunes, and calamities, and which cause sorrow, lamentation, and envy, making us envious and jealous, with the result that we become incapable of listening to reason.’

2.Taking appropriate action: ‘for we shouldn’t be unfeeling as statues, but should preserve our natural and acquired relationships, as one who honours the gods, as children of parents, as a sibling, as a parent, as a citizen.’

3. Maintaining constancy: ‘so that even when we’re asleep, or drunk, or depressed, no untested impression that pops up may catch you off-guard.’ (ED 3:2, 3-5.) This third part is intended for those are more practiced and making progress, but who still need to keep up the good work.

Armed with these instructions, let’s make an exploration of these virtues.

6th Step MODERATION Verses 10-11

Take into you what I have said.

Using the power of control to master

Your appetite, your sleep, your sexual urges,

and lastly, your competitive desires.

OVERCOMING THE HABITUAL WITH HABIT

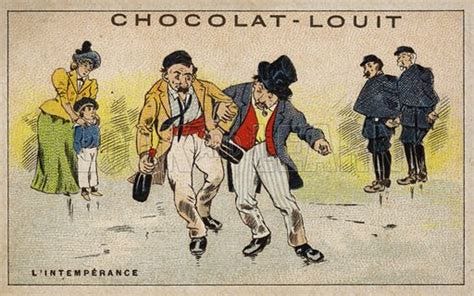

Virtue is not a word that is often bandied about today, and of all the Cardinal Virtues, the first of these, Temperance or Moderation, is probably the least popular virtue in our age, where common expressions of our culture reveal our preoccupation with excess: ‘over-egging the cake,’ ‘pushing the boat out,’ ‘bigging ourselves up, ‘binge-culture’ and the like.

Taking the instructions deeper into ourselves, we have now to learn control of our basic drivers, the ones who rule the roost out of habit: our eating which can go out of control into gluttony; our sleeping which can lead into sloth and neglect of our duties; our sexual urges which can quickly slip into the degredations of lust, and our competitive desires. What I have translated as ‘competitive desires’ here is a much more complex thing than just the physical appetites. The Greeks viewed our desire to come out on top, our need for things, our cravings for prestige, honour and ambition, and our stubborn adherence to fighting, our aggressive reaction against what threatens to overcome us, as ‘thymus’ or ‘the spirited part.’ This is not the same as ‘the Spirit,’ but rather that competitive part of us that fights with everything and everyone who tries blocks our desires – in short, that which is most difficult to overcome in ourselves. It is the same anger that arises in us when we are thwarted in our desires as the toddler does, having a tantrum at the check-out because his mother will not buy him the sweets.

These four tendencies are the ones that are hard-wired into us, to be the first to eat and drink, to feed our desires without check, to satisfy our sexual needs, and to protect ourselves against others who might compete with us for all these things or more. These drivers underlie our acquisitiveness, our boastfulness, our anger, our craving for notice and attention, leading to the slippery slope of total reactiveness.

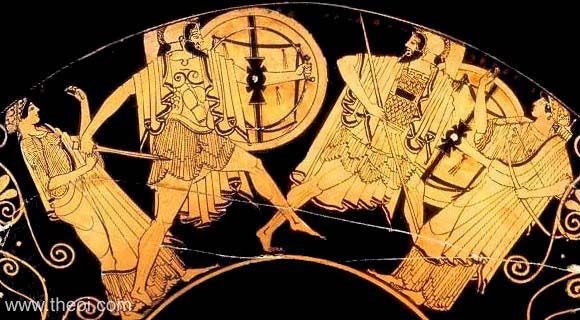

The 3rd century Cynic philosopher, Crates of Thebes, believed that treating the passions with moderation created a boundary that ‘saves households and cities,’ while Iamblichus likened the actions of moderation to the hero Perseus who ’ascending to the highest pinnacle of excellence in moderation, under the guidance of Athene, cut off the head of the Gorgon, which I take to be the power that drags us down into matter and petrifies us through mindless indulgence in the passions.’ (p.9 Iamblichus Letters)

Whatever desire presents itself to be exercised, we are invited to check out what kind of impression it shows to us. Epictetus advises us, ‘don’t allow it to lead you on by forming an image of what might follow the desire, or else it will take possession of you and lead you wherever it likes.’ We all try and sometimes fail, and so we need to realise that such failures will often be the case at the beginning of our efforts to master desires. But we don’t also have to explain and justify our behaviour as well: we only need to go back to the drawing board and examine the nature of the desire, starting over and bringing ourselves into a better place next time we are tempted. (ED2:18,23-31) Or, as Hesiod says, ‘Who ever delays his work is forever wrestling with ruin. (Hesiod: Works and Days 413)

As you will appreciate, any habit that we made and allowed to inhabit us, has to walked back to the same degree and number of times to the point of eviction: and even then, it is tough. This is why we have to harness the power of habit, and accustom ourselves to keeping an eye on how our appetites and desire are leading us.

SEXUALITY

When we are young, we cannot help looking, we cannot help falling into lust with every beautiful young person who drifts into view. While it may get easier as people age, lust of the eyes doesn’t necessarily die away. And when there is provocation? Well!

Epictetus writes about how he deals with this: ‘Today I saw an attractive boy or woman, and I didn’t say to myself, “Oh, if only I could sleep with him or her”, or “I think her husband must be a happy fellow!” – because I might as well have said, “Happy is the adulterer!” I didn’t even go on to imagine what follows next: the woman being with me, and undressing, and lying down beside me. I congratulate myself and say, “Well done, Epictetus, you’ve found a solution (to this problem.)” However, what if the girl be willing, and gives me the nod, or sends for me, and grabs hold of me, pressing herself against me, and I still manage to hold off?.... How is this to be managed, then? Make it your wish to finally be contented with yourself, make it your wish to appear beautiful in the eyes of the gods; you must aspire to become pure in accord with what is pure in yourself and in accord with the gods. As Plato says, “Then whenever this kind of impression assails you, go and offer an expiatory sacrifice; visit the temples of the gods who avert evil, as a suppliant go!’ (ED 2:18,14-19).

Epictetus goes on to instance Socrates’ personal victory over his own attraction to the beautiful young Alcibiades, which he resisted, despite his instinctive desire towards him, as they walked and rested in nature at midday, ‘Watch Socrates as he lies down (on the ground) beside Alcibiades and makes light of youthful beauty; consider what kind of a victory that was – worthy of the Olympic Games, ranking him among the successors of Heracles.’

Given the famous double standard of the ancient world, when it came to equality of the sexes, we find in the Pythagorean model of family life a typical moderation of sexual morals, which seemed to follow the Spartan custom. Instead of a young woman just into her puberty being married off, the Pythagorean woman was allowed to properly mature, becoming married at about 18, with an interval of childbirth of about four years, since it was suggested that sexual relations take place only in the winter and that moderately. (p.24 Sarah Pomoroy, Pythagorean Women).

Also, in a world where sexual relations, menstruation, and childbirth were generally seen to be polluting, a Pythagorean woman was considered to be as pure after arising from relations with her husband as she was before doing so, and therefore fit to go immediately to the temple and make a sacrifice, which tells us that, for ordinary Greek women, female attendance at a temple was probably determined by rites of purification after sexual relations or menstruation. Under the rule of Pythagoras: ‘If a woman comes from her husband, she is allowed on the same day to go to the holy shrines, but if she comes from a man who does not belong to her, never.’ (ibid) So we see that it is not the sexual act in itself that causes pollution, but the breaking of an oath of fidelity that determines pollution.

In our own highly sexualized world, the abuses and imbalances of sexual behaviour are still working their way out towards balance, we hope, but against this stands the addictive power of filmic pornography becoming, in many countries where sexual education is not given to young people, pornography horrifically becomes a benchmark of ‘what is normal’ in loving relations. It does precisely what Epictetus warns us against: the fostering of images and the brooding upon them that leads to acts by which we are led away from balance into the hinterland of self-harm, mutual cruelty, or unconsensual acts of such depravity that our minds become a breeding ground of degredation. With Iamblichus, we can agree that this, along with the other drivers of passion need to be dealt with forthrightly:

‘By every means and device, banish, cut away with iron, burn out all of these: disease from the body; ignorance from the soul; extravagance from the appetites; sedition from the city; discord from the family; and a lack of moderation from everything in general.’ Iamblichus: (VP, 7)

ANGER AND COMPETITIVENESS

So how do we deal with anger and on losing temper? Epictetus tells us:

‘When you lose your temper, you need to recognize not only that something has happened to you right now, but also that you’re reinforced a bad habit and added fresh fuel to the fire…. First of all, keep calm, and count the days since you last lost your temper: “I used to lose my temper every day, and after that, every other day, then every third day, then every fourth.” And so, if you continue in such a way for thirty day, then offer a sacrifice to the gods, for the habit is first weakened and then completely destroyed. (ED 2:18,5,14,) The advice sounds strangely reminiscent of the 12 Step Programme for people battling addiction.

But then, the 1st century CE, Greek physician, Galen himself gives us a prescription that we are already taking! Galen was once consulted by a man who had great trouble controlling his anger and who had just seriously injured a servant as a result: the man begged him to flog him to help quell this violence within himself. Galen refused, instead advising him:

‘strive to hold the impetuosity of this power in check before it grows and requires an unconquerable strength, for then, even if you would do if you want to do so, you will not be able to hold it in check…First, we must not leave the diagnosis of these passions to ourselves, but we must entrust it to others; second, we must not leave this task to anyone at all but to older people who are commonly considered to be good and noble. people to whom we ourselves have given full approval, because we have found them free from these passions. We must further show that we are grateful to these people and not annoyed with them when they mention any of our faults; then too, you must remind yourself of these things every day; if you do frequently it will be all the better, but if not frequently, at least do so before you begin your daily tasks and towards evening before you were about to rest. You may be sure that I have grown accustomed to ponder twice a day on the Golden Verses attributed to Pythagoras: first I read them over, then I recite them aloud.’ (Galen, On the Passions, pp48-49 trans Paul W Hawkins, Columbus, Ohio State University press, 1963.)

Epictetus is concerned that we retain our humanity when the habits come calling:

‘Take care that you never act like a sheep; or else in that way you would’ve destroyed what is human within you. But when do we act like sheep? When we act for the sake of our belly or genitals, when we act up random or in a disgusting way or without proper care, to what level have we sunk to that of sheep? What have we destroyed? That which is rational in us. When we behave aggressively and harmfully angrily and forcefully to what level have we sung? To that of wild beasts. There are also among us those who are large ferocious beasts, well others are little beasts small and evil natured animals which prompt us to say, I’d rather be eaten by a lion! It is by such behaviour that the human vocation is destroyed.’ (ED 2:9,4)

In all of this, the moderation of our habitual response to our desires and passions is being stressed so that these very ordinary and normal parts of life may be kept in a healthy light, without excess or addiction.

Porphyry, writing home to his wife, Marcella says to her, ‘Let us neither accuse our flesh as the cause of great evils, nor attribute our troubles to outward things. Rather let us seek the cause of these things in our souls, and casting away every vain striving and hope for fleeting joys, let us become complete masters of ourselves. For a person is unhappy either through fear or through unlimited and empty desire. Yet if you bridle these, you can attain to a happy mind, but in as far as you are in want, it is a true forgetfulness of your nature that you feel want. For hereby you caused yourself big fears and desires and it will better for you to be content and lie on a bed of rushes and to be troubled, though you have a golden couch and a luxury table acquired by labour and sorrow.’ Porphyry, Letter of Marcella 29

Let’s be clear, the whole Pythagorean idea of moderation is not to despise the good things of life – whether it be the excellent food at the restaurant, the embrace of a partner, or a success that we have enjoyed. As Hierocles tells us, we just need to understand that lack of moderation in small things can lead to ingratitude to the gods, conflict in families and war among neighbours, the betrayal of friends, and all kinds of lawlessness. (GV 8,4) Lack of temperance becomes a starting gate for things we really do not wish to be running against in life.

§ Consider §

· Look at Epictetus’s questions in the introduction to part 2 above and try answer them on specific disatisfactions that are going on in your life. This is the first step to self-knowledge, but certainly not the last.

· Where do you most need to exercise moderation in your life? What are the trigger points that you need to observe and avoid provoking or hosting?

· What are the books that feed your soul before you sleep?

· Looking over your day today, where have the four cardinal virtues been absent or half-heartedly applied?

· Where have appetites, desires, and a desire to be right, or on top led you?

· Looking over the national or world news this week, where have the desires of greed, sloth, sexual excess or abuse, and competitive ambition been playing out? What do you see resulting from them?

MEDITATION

‘Desire itself is a tendency and impulse, either for gratification or a disposition for experiencing sensation. A desire for opposites to what one is feeling now can arise from depletion, an absence of sensation, or a lack of things. This emotion is complex – perhaps the most complicated of those that arise in a human being. Most human desires are acquired and developed by a person themselves; which is why this emotion needs the greatest care and attention, and requires no ordinary body training. When the body is empty, desire for nourishment is natural; when it is filled, then the desire for food’s evacuation is also natural. But the desire for needless nourishment, for unnecessary bedding and clothing, or needlessly expensive housing is also acquired. It extends to furniture, drinking cups, servants, and animals raised for food. Of all the human emotions, generally speaking, desire is content almost never, but continues on into infinity… There is nothing too ridiculous towards which the soul of children, women and men will not hurtle.

- Iamblichus: VP, 31, 205-7