As we approach Justice, we find many of the previous verses falling into place and making sense, which is one of the gifts of just reasoning. As threat of war and changes in the balance of world power gather on the horizon, we need to hold to the true practice of justice in every part of our lives. In this step we follow the paths of Themis and Dike in our meditation and begin to understand how we can practice justice in both word and deed.

§ Step 8. Practice justice in both word and deed. §

Verse 14: The Golden Verses

JUSTICE

Everything we do, think, or say has effect somewhere, sending its ripples into the universe. We are reminded once more of Step 2: ‘Honour and revere the Oath,’ where we discovered that our commitment to the Oath is what holds the whole Cosmos together. Justice is the immortal balance of all things, and is seen by Hierocles as the most perfect virtue, since it combines the three other Cardinal Virtues:

‘We need a tetrad of virtues to be able to turn away from the vices,’ so that we can apply wisdom to our reason, courage to our wilfulness, temperance for our appetites, and justice which coordinates the Cardinal Virtues within us. (GV 10,1)

Justice as a coordinator of the virtues of courage, temperance and wisdom seems fine in theory, but the instruction of this verse is to ‘practise justice in both word and deed. Deed.’ What will this entail? Where and how can we do this? Our everyday life is, of course, the primary arena for practising justice, but finding parameters of justice may remain utterly theoretical until we start to apply its principles.

At base, justice is about respect and includes everything that the Oath contains. This immediately gives us the shape of our practice: it includes every relationship that we have already looked at within part one of this course: from the Divine, the Gods, the angels, daimons and heroes, the ancestors, and our own kindred, our friends as a basic template. It also includes our own self-respect, and the respect we have to those who share this world with us, whether human, animal or environmental. Not much, then!

The way we perceive the parameters of respect is very much led by the three parts of our being: the appetites and passions that act as the basic drivers; our competitive desires which inflate us and lead us into believing ourselves as better than others; and the rational part of our soul that maintains the clarity and faithfulness to our divine belonging, and which understands that what our drivers and desires show to us is nonsense. When we overstep the rights of others, we commit injustice.

Injustice is very easy to activate, as Socrates understood, ‘To one who said to the philosopher, "Don't you find so-and-so very offensive?" his reply was, "No, for it takes two to make a quarrel." (Diogenes Laertius Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, II, 36). Being non-judgemental enables justice, while forgiveness ensures that we do not prosecute condemnatory opinions that leads us from our path. The puzzling Pythagorean saying, ‘Do not leave the any mark of the pot on the ashes,’ really signifies that, when you have had a disagreement, forgive and be reconciled, rather than maintaining the wrong or hurt of it, which would stain your soul.

This leads us back to the Oath once more, for it is by philia, or altruistic love for the cosmos, that we support the truth that lies at the heart of justice. To remain in the emotional turmoil of distress, or to relish and feed upon the hurt that has been done to us, lays us upon to something very serious indeed.

When people demand justice for something, they invariably want a layer-cake of things: restitution for things spoiled, destroyed or taken; the restoration of order and peace; a punishment commensurate with the offence or crime; and sometimes, sadly, the pure undiluted vengeance of retaliation. The earthly judiciary and the common law act as buffer zones for such expectations, and many litigants have discovered that fairness and justice do not necessarily go hand and hand.

Pythagoras stated that those who ruled as councillors in their communities ‘were to take care that none of them did anything wrong, so that the people might be motivated, not by fear at the penalty of the laws which might induce them to commit crimes if they could get away with it, but rather by shame before their noble way of life, which would induce them to strive after justice.’ (Iamblichus VP 9, 48.)

But what happens when the councillors or governors of a nation are themselves shameless, blind to their own injustices, and consciously or unconsciously prosecuting their own selfish ends? Well, we have seen how that is working out throughout the world. Those who live under such regimes are the most unfortunate of people, subject to injustices, terrorism and coercion.

In such times and places, where the horrors of genocide, persecution, the suppression of freedoms, and lack of care for the innocent, we turn to restorative justice – as in South Africa and Northern Ireland where the practice of Peace and Reconciliation has enabled both sides to withdraw from the retaliatory patterns of tribal vengeance, by understanding how each side can be blameful and hurt, and how to pass beyond prejudice and tribal justification into being fellow human beings together again. But that is a process that comes after the injustice, and there are still many places in the world where the enforced or ongoing separation of both sides still requires engagement: as in the Balkans, in Ukraine and in Gaza, for example.

What is our part in practising justice?

BECOMING A PURPLE THREAD IN THE GARMENT AND REMEDIAL JUSTICE

The greatest justice is to remain true to ourselves and the divine vocation that is within us. That shining gift illuminates our world, and to deny it is death, for it is the reflection of the divine that guides the soul: a respect that dwells within us as the reminder of how to act. Our soul’s vocational calling is something we which we remain true. Here Epictetus reveals Socrates defending himself and his philosophical calling at his trial in the following way: his care for his fellow citizens has been his guiding recollection:

‘Did Socrates enable all who came to him, to take care of themselves? Not even one in a thousand; but being, as he himself declares, divinely appointed to such a post, he never deserted it. What said he even to his judges? "If you would acquit me, on condition that I should no longer act as I do now, I would not accept it, nor desist; but I will accost all I meet, whether young or old, and interrogate them in just the same manner; but particularly you, my fellow-citizens, since you are more nearly related to me."

"Are you so curious and officious, Socrates? What is it to you, how we act?"

"What say you? While you are of the same community and the same kindred with me, will you be careless of yourself, and show yourself a bad citizen to the city, a bad kinsman to your kindred, and a bad neighbour to your neighbourhood?"

"Why, who are you?"

‘Here one ought nobly to say, "I am he who ought to take care of mankind." For it is not every little paltry heifer that dares resist the lion; but if the bull should come up, and resist him, would you say to him, "Who are you? What business is it of yours?" In every species, man, there is one quality which by nature excels, - in oxen, in dogs, in bees, in horses. Do not say to whatever excels, "Who are you?" If you do, it will, somehow or other, find a voice to tell you, "I am like the purple thread in a garment. Do not expect me to be like the rest; nor find fault with my nature, which has distinguished me from others."’ (ED 4:1, 19-23)

We may well ask, with the accusers of Socrates, ‘What is it to you, how we act?’ Well, consequences come of our actions, thoughts, desires, words, is why. For Neo-Platonists, the Cosmos itself is a living being – in Plato’s Timeaus, it is called Auto-Zoon or ‘Animal Itself.’ Every being within Animal Itself, our dear world, has its own nature. The garment of flesh that covers all of us is not all that comes with us when we are born, we also have the ‘purple thread’ of our soul which reminds us of our original condition. It is the soul that knows justice is nothing other than the divine truth.

Socrates held firm to the understanding that, ‘True justice is not harming anyone, even if that person is considered an enemy.’ (Plato, Republic, 336a) This understanding finally led him to his trial, unjustly accused. While he could have escaped and run away, he did not, but faced his unjust accusers with the same obedience to his own nature, and with perfect justice. You can read an account of Socrates’ response to his accusers here in the Apology of Plato, which is too long for our consideration here. It is one of the finest responses to injustice ever made, complete with the kind of humour that only a philosopher can muster: https://classics.mit.edu/Plato/apology.html

Throughout Neo-Platonic understanding runs the assertion that justice is supreme and that punishment is remedial, helping to reform the human being whose deeds have warped the trajectory of the soul. In the following passage, Plutarch’s Moralia, we see that some laws are determined by the Gods, while some are evoked by human beings for orderliness among ourselves, but that others are shored up by local custom or cultural conventions that often seem bizarre to those who live elsewhere. Plutarch starts with the analogy of the medical treatment that physician applies to his patient:

‘And while one that understands nothing of science finds it hard to give a reason why the physician did not let blood before but afterwards, or why he did not bathe his patient yesterday but to-day; it cannot be that it is safe or easy for a mortal to speak otherwise of the Supreme Deity than only this, that it is the Deity alone who knows the most convenient time to apply most proper corrosives for the cure of error and impiety, and to administer punishments as medicaments to every transgressor, yet being not confined to an equal quality and measure common to all distempers, nor to one and the same time.

Now that the medicine of the soul which is called justice is the most transcendent of all sciences, besides ten thousand other witnesses, even Pindar himself testifies, where he gives to God, the ruler and lord of all things, the title of the most perfect artificer, as being the grand author and distributer of Justice, to whom it properly belongs to determine at what time, in what manner, and to what degree to punish every particular offender. And Plato asserts that Minos, being the son of Zeus, was the disciple of his father to learn this science; intimating thereby that it is impossible for any other than a scholar, bred up in the school of equity, rightly to behave himself in the administration of justice, or to make a true judgment of another whether he does well or no.

For the laws which are constituted by men do not always prescribe that which is unquestionable and simply decent, or of which the reason is altogether without exception perspicuous, in regard that some of their ordinances seem to be on purpose ridiculously contrived; particularly those which in Lacedaemon the Ephori (the five Spartan magistrates) ordain at their first entering into the magistracy, that no man suffer the hair of his upper lip to grow, and that they shall be obedient to the laws, to the end they may not seem grievous to them. So, the Romans, when they asserted the freedom of any one, cast a slender rod upon his body; and when they make their last wills and testaments, some they leave to be their heirs, while to others they sell their estates; which seems to be altogether contrary to reason.

But that of Solon is most absurd, who, when a city is up in arms and all in sedition, brands with infamy the person who stands neutral and adheres to neither party. And thus a man that apprehends not the reason of the lawgiver, or the cause why such and such things are so prescribed, might number up several absurdities of many laws. What wonder then, since the actions of men are so difficult to be understood, if it be no less difficult to determine concerning the Gods, wherefore they inflict their punishments upon wrongdoers, sometimes later, sometimes sooner.’ (Plutarch De Sera, 4)

Similar local customs surrounding justice and punishment often seem barbarous to us even in today’s world, because they originate in ancestral codes and viewpoints. But the remedial corrective of Justice to our disordered condition is not just applied to our lack of civil virtue in daily life but, as Thomas Taylor, the great 18th century translator of Plato writes, ‘The soul is punished in the future for crimes committed in the present life; but this punishment is not perpetual; the divinity punishing not from anger or revenge, but in order to purify the guilty soul and restore her to the proper perfection of her nature.’

The remedial justice that acts upon the soul is something that we shall be scrutinizing in future parts of the Golden Verses, while we will be introducing those beings whose oversight shapes the parameters of our lives in the next step. Such considerations of justice are not popular in our time, brought up as we are in a world that has largely inherited a retributive and religious reward/punishment system towards the soul, where the good are rewarded while the bad punished, but forever, in both instances. While there are still elements of this understanding in the Classical world, the NeoPlatonic view, is rather that our subsequent reincarnations are punishment enough. We will be looking at these also in steps to come.

Following a philosophic lifestyle, as well as being initiated into the Mysteries were seen as ways of avoiding the chasmic fall into oblivion of soul, or the consequences of following a disordered existence. To set one’s feet on the royal road of the gods enabled the soul to find its way so that made its way back to the divine instructions of the soul which could be recollected. And while many took that route with heartfelt commitment, others had the heady expectation that they might follow it adequately if they just took the coloration of a philosopher or one of the mystes, rather than actually commit to that life-style, which leads us to ask the question….

WHAT DOES A REAL PHILOSOPHER LOOK LIKE?

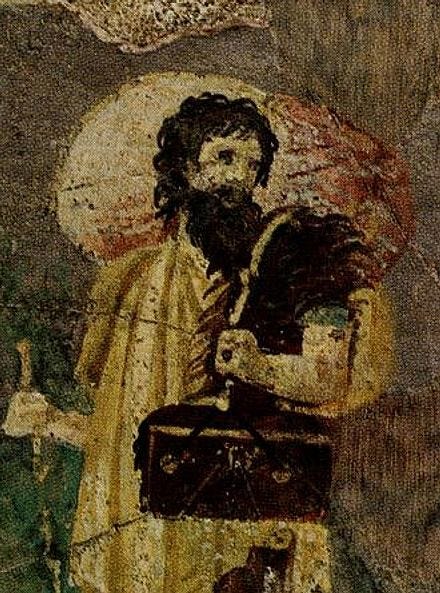

In Classical Greece, everyone knew what a philosopher was supposed to look like this: this picture is of the Cynic philosopher, Crates of Thebes (c. 365-285 BCE.) whom Plutarch described as, ‘with only his wallet and tattered cloak, laughed out his life jocosely, as if he had been always at a festival,’ freely entering the houses of his friends without invitation. His appearance was what people expected philosophers to look like.

Crates

Like the dust-coloured loin cloth of the ascetics of India, or the long-haired colourfully-clad hippy of our own era, the philosopher’s beard and rough cloak were like a kind of uniform, almost a cliché. Epictetus has fun considering this question, how do we know who is a philosopher?

‘No sooner have they put on a rough cloak and let their beard grow than they proclaim, “I’m a philosopher”, yet no one is recognized as a musician because they have bought a plectrum and a lyre, or is seen as a blacksmith because they have on a felt cap and a leather apron.’ (ED 4:8, 15-16.). He goes on to say, ‘No sooner do people feel drawn towards to philosophy - like people with weak stomachs to food that they’ll soon come to loathe - expecting soon to acquire the sceptre and the kingdom (of philosophy). They let their hair grow, assume the cloak, and bare their shoulder to wrangle with all they meet. And if they see anyone in a thick warm coat, they have to wrangle with them. But first harden yourself up against the weather… First study to conceal what you are, philosophise first with yourself for a while. For any plant to grow needs first to have its seed planted in the earth, and to lie hidden there, so that it can grow by degrees.’ (ED (4:8, 34-36.)

Yet Socrates himself was a bare-foot philosopher who was known everywhere as ‘the gadfly,’ due to his waspish wit and unyielding elenchus – his ability to deeply question anyone with whom he came into conversation so that they saw another view. By loosening the grip of people’s carelessly-held opinions, he led them to deeper self-knowledge by dint of dialectic or the working out of reason. Socrates could often be seen standing still, looking into the middle-distnace of a vision that held him for hours at a time; he was continually looking to be of service to his fellow citizens, not sparing his own life to that very end.

Socrates (c.470-399 BCE) is regarded as the father of Western philosophy, but he himself would readily have readily acknowledged all who preceded him. His parents were a stonemason and a midwife, and he was an Athenian citizen, but his main task was the education of the soul. His life came to an end due to false charges of impiety and corruption of the young. Condemned by the city state that he had often criticised and yet served well, his fate was to drink hemlock as part of a state execution. His long stay in prison before his execution and his conversation with his followers who visited him there is the subject of Plato’s Phaedo. (You can read this dialogue here: http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/phaedo.html)

Plato makes Socrates the mouthpiece of his philosophical works, wherein his mentor dialogues with many individuals in ways that demonstrate his philosophical method. While Socrates did not record his teachings, very many other individuals did, and while we cannot put a pin between what he said and what Plato put into his mouth in many cases, the main facts and features of Socrates’s life and teachings come through to us in unforgettable ways.

Socrates, an impression by Robert Kubis.

No, Socrates is no model of beauty: his beauty was all within. His young protegé

Alcibiades, did not let Socrates rejoice in any illusions about his appearance. In Plato’s Symposium (251a) he says this of him: "I say, then, that Socrates is most similar to those Silenuses that are seated in the workshops of statuaries, which the artists have fabricated with pipes or flutes in their hands; and which, when they are bisected, appear to contain within statues of the Gods. And I again say, that he resembles the satyr Marsyas. That your outward form, therefore, is similar to these, O Socrates, even you yourself will not deny; but that you also resemble them in other things, hear in the next place." And a little later Alcibiades says (216d), "...and again, he knows all things, and yet knows nothing; so that this figure of him is very Silenical; for he is externally invested with it, like a carved Silenus. But when he is opened inwardly, would you think, O my fellow guests, how replete he is with temperance?...but when he is serious and is opened, I know not whether any one of you has seen the images which are within… I however once saw them, and they appeared to me to be so divine, golden, all-beautiful and wonderful, that I was determined to act in every respect conformably to the advice of Socrates."’

As you can see from the figure of a Silenus above, these squat and ugly figures were no pin-up. They were modelled upon the original companion of the god Dionysos, the man of the forest, who could be prophetic when drink.

What made Socrates who he was, what gave him his inner beauty, was his faithful following of the cardinal virtues, which can also works for us. They are the foundation by which we can approach the Mysteries.

‘Temperance, justice, fortitude, and wisdom itself form the prelude to purification from pollution and indeed those famous people who are established the Mysteries for us seem to have been no mean thinkers… they have obscurely hinted long ago that whoever descends into Hades uninitiated and unpurified shall grovel in the mire, but whoever has been purified and initiated shall, on their arrival there, dwell with the gods. For there are, say those who write about the mysteries, that “many bear the thrysus bearers, but few are the mystes” …But into the company of the gods none may go who has not sought wisdom and departed in perfect purity, but the lover of learning.’

- Iamblichus Exhortation on to Philosophy p.49 Moore Johnson

Here Iamblichus is referring to two things: firstly, the understanding that those who had taken initiation into one or other of the Mystery cults would be treated differently in the afterlife where everything is reckoned up: you wanted to keep good connection with Persephone and Hades, her husband, because they were the ones who made the reckoning when you died. Secondly, he is referring to the Bacchic Mysteries of the god Dionysos, whose followers bore the thyrsus – a giant fennel stalk which was covered with ivy leaves and festooned with ribbons. Bacchants and Bacchantes danced in the wild places at the festival of Dionysos and, like a lot of people who are drawn to sacred festivals, Iamblicus is saying that many come bearing a thyrsus, but very many fewer are those who are initiated into the Mysteries and become mystes – a term that referred to the initiates of the Eleusinian Mysteries. It stems from the Greek meaning ‘to shut one’s eyes.’ The enlightenment of initiation was about closing your outer eyes in order to see with one’s inner eyes.

Not judging by appearances is part of our own practice of justice in daily life: what is it that we perceive underlying any personal interaction or situation? Where does Justice dwell with it?

§ CONSIDER §

· Take Justice as your theme over one whole day. This means remaining close to the principle of justice in all matters: in your dealings with everyone, in the words you speak, in the attitudes and opinions you are holding. Look over your day at its end, how did you do in your practise of justice?

· Explore your just respect for the Divine, the Gods, the angels, daimons and heroes, the ancestors, and our own kindred, your friends, your own self-respect, and the respect you have to those who share this world with you - the human, animal, environmental beings.

· Check where you are putting people and things down in order to elevate yourself higher. What is playing out here? What do you learn from looking at this?

· Were you a Silenus figure, what would be the image of the divine that might be found inside you?

MEDITATION

‘For there dwells Order with her sister Justice, firm foundation for cities,

and Peace, steward of wealth for men, who was raised with them—

the golden daughters of wise-counselilng Themis.’

— Pindar, Olympian, 13.6–8; trans. William H. Race

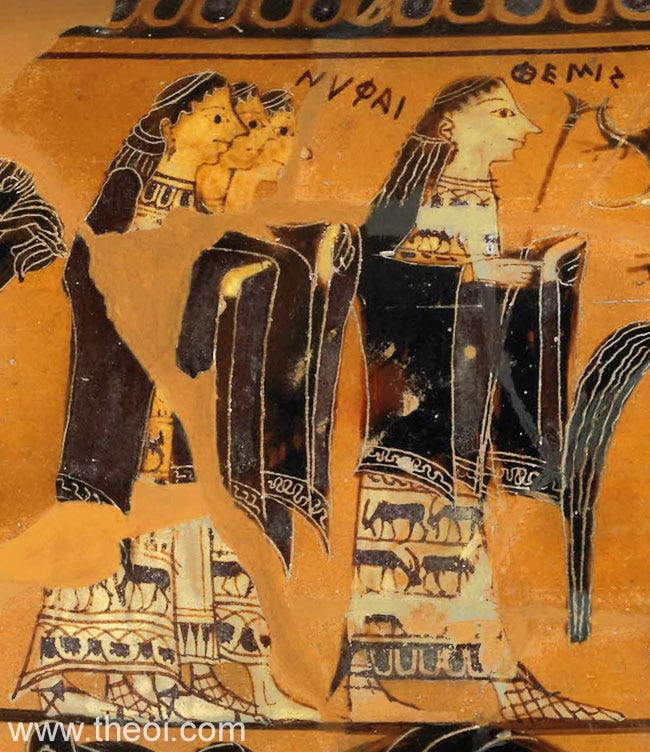

In the following short meditation, Themis is the goddess of divine justice and law, as well as of good order: she is seen as the companion and councellor of Zeus, while Dike is the goddess of justice, moral order, and fair judgement, sitting beside Pluto, the god of the underworld. Each goddess of justice sits beside the rulers of the upper and lower worlds. When you have contemplated the quotation, visualize the two goddesses of justice: the transcendent justice of Themis who sees all sitting beside Zeus, and Dike (Dee’kay) who maintains moral order sitting beside Pluto, and in whose care is the relative law of our world. Dike’s sisters are Eunomia (good order) and Eirene (peace) – together they make the Horae or ‘the Seasons’ who look after human affairs. Dike also rewards virtue. The Horae are all daughters of Themis and Zeus.

For those familiar with the Qabalistic Tree of Life, the effect of Themis is very like the influence of Chesed, the expansive sephira of benevolence and support while that of Dike is more like the sephira of Geburah, which rectifies and balances. These two forces of justice bring the balance between them.

§ ‘Every place needs justice, and human beings created the myths that just as Themis sits at the side of Zeus, and Dike at the side of Pluto, so justice sits in cities through the law. Whoever does not act justly towards what has been ordained may be said to wrong the whole cosmos.’ - Iamblichus: The Pythagorean Life 9, 46. §

Be aware of yourself sitting between the two goddesses, and experience the bond that is between them both in the upperworld and the lowerworld. Sit with this for a while, until this is clear. Now include yourself as sitting in your place in relation to them: hold in your heart whatever is needing the focus of justice at this time. Be aware of their ability to bring the balance of justice to our own world, as it flows through what you have brought to them. Your task here is just to hold focus, not to direct, influence or determine the outcome of things: leave that to the goddesses. Be still and see what unfolds. Conclude your meditation cleanly and clearly, with thanks.

Thank you for all your kind words concerning my Running Away Again post of last week. John and I are finally back home and catching up with our lives again.

I am aware that Courage is displaced from this study of the Cardinal Virtues, but we will pick up on it again in part 3 which starts in a fortnight’s time. I would very much like to do a chat with you but my breathing remains very troublesome, and I’m hoping for some better medical intervention soon, as no one seems able to diagnose me currently.

Just got his now... looking forward to reading it properly! ***