Part 3 of our course looks squarely at those things that people generally think of ‘the unfairness of life.’ The verses in this part cover the consequences of thoughtlessness, death, loss, suffering and how we remedy our lot. The Neo-Platonic understanding of these misfortunes falls under a consideration of what Reason, Necessity, Providence, Fortune and Fate weave together and how these shape our lives through the medium of our choices - both the ones we make in our present life, and those which have taken in former lives.

We take a deep step into this very different world-view, as it provides us with some extraordinary realisations that are not commonly part of the Western world’s understanding. If these ideas sound, to our ears, nearer to Eastern aspects of reincarnational belief, then that is because they are. Greek belief was blent of many different sources: its folk-beliefs and native religious rites, as well as the influence of Egyptian, Babylonian and wider understandings that those initiated into those mysteries bestowed upon it. Before Christianity erased its most obvious traces, reincarnation was firmly part of the Western heritage.

This introduction to the bigger concepts is followed by a study of why reason and wisdom have to be our better choices in a world woven by so many strong factors. Please take your time to digest all this, and sit with it in meditation.

PART 3 NECESSITY, PROVIDENCE, FATE AND FORTUNE

Pythagoras’ starting point for the care of human beings was ‘to learn the truth about our previous lives. It was his practice to remind any who met him, most distinctly and clearly, about the former mode of life their souls lived long ago, before being bound to their present body, and demonstrated with convincing proofs that he himself had been Euphorbus son of Panthous, the conqueror of Patrocles. (the companion of Achilles, from the Iliad.)’ (Iamb PL 14,63). Marinus, in his Life of Proclus, recalled that Proclus had a dream that the soul of Pythagorean Nicomachus lived in him.

We do not know by what means Pythagoras caused remembrance to surface in his followers, but this kind of necessary recall has been the part of the training of the Western Mystery schools for over a hundred and thirty years. My own teachers and their teachers’ teachers believed it important as part of the process of self-knowledge.

Reincarnational remembrance is not something that an unprepared person might cope with, for the download of such knowledge takes a great deal of assimilation, in my experience, and those who dabble in ‘a little quiet regression’ to accomplish this often discover one of two things: they are either shocked rigid by any revelation, which is not always a carefree memory, and so they leave the whole thing alone, or else they discover any number of prestigious and exciting lives and become addicted to the process, in a wish-fulfilling way.

Knowledge of past lives alone is not the point: it is the wisdom that is gained from such an exploration that enables us to understand much. Memories may be sporadic or fleeting. In my own case, memory has been evoked from the performance of physical actions, gestures, or procedures which have produced clear and consistent verifications for me. These have explained clearly to me why my apparent understanding of some abstruse or arcane knowledge has been recollection, rather than an unmotivated accessing, and that much of my current life has been a recapitulation of things learned much earlier on. The ability to live our life ethically by the guidance of former teaching still requires application, however.

Reincarnation – the serial rebirth of the soul into another body - and metempychosis – the movement of the soul from one form of body into another – have both been part of the Western tradition for as long as they have been in the East. To many, it may seem like a wild and woolly idea that civilization has kindly purged from our minds, something which has no part in the nice tidiness that academic philosophy has fostered over the last centuries, but here it is, bang in the middle of things after all! Of course, it is the very primal wildness of reincarnation that helps us deal with a multitude of things that are too difficult to stomach or to understand. It takes an axe to the neat orderliness of our lives and gives us a whole forest of possibility to deal with! The dry, rational academic view of philosophy is often completely detached from its roots, and frequently forgets its earlier origins. As wcholar Dominic O’Meara has stated, ‘all Greek theology derives from Orphic mystagogy: Pythagoras first learning from Aglaophemus the secrets concerning the gods, (with) Plato after him receiving the complete science of the gods from Pythagorean and Orphic writings. (trans. D. O’Meara Pythagoras Revived: Mathematics and Philosophy in Late Antiquity. 1989, Oxford: Clarendon Press. I 5, 25, 24–26, 9). The memory of ancient rites and traditions, fortunately for us, usually lodges in myth where it can be seen more clearly.

When reading the following section, please remember that ‘myth is something that has never happened and is happening all the time’, in the words of Sallustius. (Concerning the Gods and the World.) While ‘myth’ is often taken in modern parlance to mean ‘a lie, or misapprehension’, I would recommend that you take myth it as ‘a story that tells us a truth that is true in all ages.’

Before we were born, we are already forming patterns, according to the myth that is given by Plato at the end of his long dialogue on the creation of the perfect state, the Republic. The Myth of Er tells how, after being injured in battle, and left unconscious in a pile of dead bodies, the soldier Er is taken up with the released souls of the slain, and witnesses their experiences after death. Just as he is about to be burned upon his pyre, Er revives and gives the following account. This is but a short summary, but you can read the entire passage here, for it contains some of the most engaging accounts of the process of transferring from one life to another: https://eurosis.org/cms/files/projects/Plato_Republic_HB.pdf

§ § §

On opening his eyes to his vision, Er saw two openings in the earth and two others in the heaven. The souls were judged as just or unjust, with the just went by the right hand way and the unjust by the left hand one. The guardians of these portals bade him follow the right hand opening and become ‘the messenger to humanity’ and to note and report what he was shown. He saw those coming down from heaven as pure souls while others were coming up from Hades met in a meadow where they could converse for seven days, after which they went onwards either to birth or to judgement. On passing through the portal towards heaven, Er saw suspended in the heavens the great Spindle of Necessity whose shaft was lodged between the knees of the goddess, Nyx or night while, emanating from the eightfold whorl, sounded the music of the spheres. Around the Spindle saw the Moirae or Fates, daughters of Necessity: Lachesis, Clotho and Atropos who sat enthroned singing, respectively, the song of what was, what is, and what will be.

From the lap of Lachesis, the guardian prophet took up bundles of lots each representing a future life, and randomly strewed them about, bidding each soul chose one lot for their next life. The souls were told to choose both their own daimon and their own life, to which they had to faithfully cleave, from the lots thrown near them, but Er was not permitted to choose, since he was still living. The souls were told that the lots gave random lives – some ordinary lives, some of great tyranny, pain, or hardship, so they were bidden to choose well. Some without due attention drew horrific lives. Those who had suffered previously made more moderate choices. The soul of Orpheus chose to be a swan, while that of Atalanta chose the life of an athlete. When each had chosen, they went to Lachesis who sent the soul with its guardian daimon, who would oversee their life, to Clotho who ratified the soul’s destiny, then onto Atropos who made that destiny irreversible.

After passing under the throne of Necessity, the souls came to the Plain of Oblivion, encamping by the river of forgetfulness. Those who drank deeply of its waters forgot their former life, those who drank sparingly remembered a little more. The souls then slept and were wafted towards the kindred star and came to be conceived and reborn. It was at this point that Er came to himself upon his funeral pyre and awoke.

§ § §

A complete study of this myth is beyond the scope of this course, but I do encourage you to return to it and read it in full, in your own time. While we will look closer at the durations and particulars of the after-life processes outlined in this myth at a later date, we note that all souls pass under the throne of Necessity or Ananke, like the children of a mother between whose knees we were all born.

We also notice that Orpheus consciously chooses the life of a swan: it is not a coincidence that the swan/goose in Hindu belief is Hamsa, the symbol of eternal life, and the ultimate reality or Brahman, perhaps revealing that Orpheus no longer has to be reborn and, in harmony with the Orphic dictum, he has ‘flown out of the weary wheel’ of rebirth. Just as the swan/goose is equally at home in water as on the land or in the air, so the Hindu term paramahamsa is given to the achieved yogi or, as we might say, philosopher. The Paramahamsa Upanishad tells us that such a one,

‘does not fear pain, nor longs for pleasure.

He forsakes love. He is not attached to the pleasant, nor to the unpleasant.

He does not hate. He does not rejoice.

Firmly fixed in knowledge, his Self is content, well-established within.

He is called the true Yogin. He is a knower.

His consciousness is permeated with that, the perfect bliss.

That Brahman I am, he knows it. He has that goal achieved.’

— Paramahamsa Upanishad, Chapter 4

In Hinduism, Brahman is the highest principle of reality, the creative principle that lies realised in the whole cosmos. This is the aim of the soul, to become part of it and we are all on that quest. It was Proclus was described the soul as ‘a far-wanderer, who descends all the way to Tartarus (the abyss where the Titans were imprisoned) only to be raised up again, who unfolds all possible forms of life, making use of diverse manners and suffering one passion after another, who takes on the forms of living beings of every sort, daimons, humans and irrational creatures, and yet is guided by Justice, ascending from earth to heaven and from matter to intellect, being led round and round in accordance with certain prescribed revolutions of the universe.’ (Proc In Tim. 3. 259.21-7)

We will be following this progression of the soul throughout this course, bearing in mind that all myths about the after-life offer us a model that helps us conceptualise principles that are hard to envisage or understand, and that all such models of the processes and sequences of the soul after death are just that. Whether we look into Tibetan, Hindu, Egyptian, or Celtic models, they will all show us something that the soul knows to be true from its own voyages through reincarnation, with several variations that we even find within Platonism itself, for this myth is just one version that Plato himself wrote down; in the dialogues of Gorgias, Phaedo and Phaedrus we find yet more. But now, we need to look more closely at the some of the guardians of our lives, some of whom we have already met in this myth.

THE SHAPERS OF LIFE

The 9th century Byzantine bibliophile Photius introduces us to some of the mighty beings who shape our life, in his appreciation of Hierocles’s writing:

‘But the God, who is the creator and father reigns as king over them all, and his paternal royalty is Providence, or Pronoia, which decrees to each kind, what is suitable to it: and the Justice that follows upon it is called Hiemarmene, for this is not the thoughtless necessity of Ananke nor of the casters of horoscopes, nor the constraint of Bia (Force) of the Stoics nor, as Alexander of Aphrodisias thinks, is it identical with the Platonic bodies, nor is it that lot (yenesis) which is altered by incantations and sacrifices, as some think, but it is God’s justice-dealing activity, concerning those things that occur in accordance with the decree of Providence, and corrects “the things that are up to us” in order and sequence, with regard to the freely-chosen hypotheses of our voluntary acts.’ (Photius: Library on Hierocles, Codex 251)

Photius mentions a whole stream of factors and embodied qualities which are very active within Platonism. Ananke or Necessity we have already met in a previous step.

When we consider Fate, we tend to think of these ladies, the Moirai or Fates, whom we met above the Myth of Er, Atropos, Clotho and Lachesis who are the daughters of Ananke – who is also associated with Nyx or Night in later Platonism.

In our ordinary understanding of Fate, we can comprehend how it plays its part in our lives. Fate is that which we cannot change: we will always be the child of our parents; the colour of eyes, hair and skin, our physiology will be inherited from them; any diseases or conditions we may have or develop come also from that mixture of ancestry. If we factor in reincarnation into a consideration of Fate, we may also have other fateful patterns which relate to the choices, acts, intentions and corollaries of earlier lives which are also within the mix. As we saw in the Myth of Er, it is Lachesis who has the bundles of lots in her lap – the lives that we are invited to chose from, and which effectively cut us from our last life to begin a new one. While it is Atropos who assigns to us our daimon or guardian spirit to accompany that life-choice, and it is Clotho who ratifies that decision, setting our fate upon her loom. Our daimon stays with us throughout our life, even accompanying us to judgement afterwards.

I hear you cry, but what about our free will? We will be continuing our considerations below in step 9, but suffice it to say that we are given every encouragement to choose Reason and Wisdom to emend and correct what might have been an unfortunate fate. ‘Everything conforms to Fate’ (Plutarch’s Moralia, On Fate 5, 3) and acts as a kind of law, as Plato’s Laws tell us ‘ if ever there should arise a man competent by nature and by a birthright of divine grace to assume such an office (as ruler), he would have no need of rulers over him; for no law or ordinance is mightier than Knowledge, nor is it right for Reason to be subject or in thrall to anything, but to be lord of all things, if it is really true to its name and free in its inner nature.’ (Laws 875c) However, as we see all around us, such paragons are rare indeed, and most supreme rulers become autocrats, led by their lower nature very speedily, which is why laws, divine and human, are necessary.

The bounty of the divine is seen not only the Gods, but in Providence, or Pronoia, who is a goddess in her own right, whose mercy runs throughout the whole cosmos to bring benevolent help and relief, aiding the good and the unjust alike, regardless of their merits. There is no place where Providence does not reach. She is seen a saviour and deliverer, so why then does Providence not help us when we are dire straits? Proclus tells us ‘when that which is mortal in us predominates over that which is divine, then the generation of evil is effected in the soul.’ (Proclus, Doubts on Providence V, 30, 5-7.). We will become much more familiar with Pronoia as we go on further on our journey.

Finally, we have Fortune or Luck. Fortuna is one of the longest-serving goddesses who maintains a host of followers, both in the gambling world, and in everyone’s secret desire to be the lucky one in all our enterprises. She is the one who changes everything we had planned, sometimes giving us opportunities (not always conveniently) but also unforeseen accidents, missed chances, and alterations to the even tenor of events.

In the world of Tarot, Fortune’s Wheel occupies the place of the affairs of the world that subject to the vagaries of time, interval and chance. This sub-lunary goddess, similar brings changes – the occasions, opportunities, unfortunate accidents that are the very stuff of life that we say, ‘just happens.’ No-one is exempt from ‘the stuff that happens,’ of course. Her wheel is also seen as a symbol of life after life in both Western and Eastern culture. The initiations of Orphism were predicated on escaping the weary wheel of continuous lives and rebirths, much as Buddhism seeks to escape samsara.

Our whole lives are woven by Fate, Providence and Fortune, and we sharply experience Necessity every day of our existence, but we also have the possibilities that reason can provide by way of mitigation. So now we turn to reason, which is a way of turning back to the cardinal virtue of wisdom..

Here is my song about the Spindle of Necessity from my album, Deep Well in the Wild Wood, available from me here: http://www.hallowquest.org.uk/product.php?id=153&pageid=5170

SONG of the SPHERES: by Caitlín Matthews. The spindle it is turning, Turning between the knees of Night, Her own three daughters yearning, For the fate of the thread so bright. And the siren voices singing, Each voice about the eight-spun whorl, Eight pure star-notes ringing, A single harmony of pearl. Lachesis notes the passing, Clotho weaves the present web, Atropos notes the coming, Of the eight-fold gifted thread. Turn, O turn, the whorl of singing, Let us know each gifting star, Learn, O learn, the song's beginning, We remember from afar. Selene brings us sleeping, Helios brings the gift of mirth, Aphrodite's heart is keeping, Hermes carries speech to earth. Ares' fire is the kindling, Zeus the life-breath of each birth, Cronos brings the gift of grieving, To all mortals bound for earth. But the radiant lady shining, Queen of every blessed night: Urania's constellating, Keeping harmony arright. She the wisdom of our weaving, Sings the planets to their rest: She the octave, she the reiving Goddess of the earthly guest. Sources: The Republic (Myth of Er) & Kore Kosmou

BEHAVING WITH REASON

Step 9. Accustom yourself not to act thoughtlessly.

– Verse 15

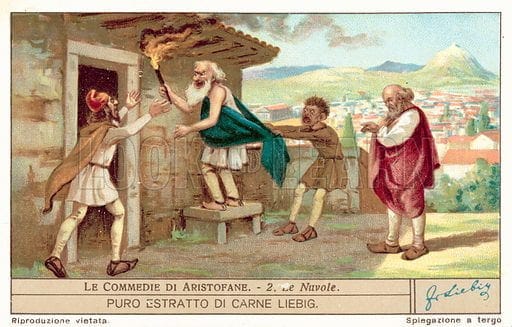

The final scene depicted above is from Aristophane’s satiric play The Clouds, first shown in 427 BCE. It shows the burning down of the ‘School of Thinkery’ run by Socrates and his pupils, by a frustrated Strepsiades, whose son Pheidippides has gone from being a debt-ridden, horse-racing maniac, to an equally-obsessed sophist under Socrates’s influence. The play mocks and satirises the concerns of philosophers - from the close study of the natural world by the pre-Socratic philosophers like Anaxamedes who posited that ‘all things were air’, to ‘the longing for wings’ as a philosopher’s final goal. It failed as a play, probably since the aim of any pastiche requires the audience to fully understand the original which is being parodied for comedic effect.

The Clouds certainly stands what we are doing in this course on its head, casting Socrates as a caricature of himself, making him appear to be a fraudulent and misleading teacher, and mocking the new ideas that late Platonism would finally establish. Many scholars regard this pastiche of Socrates’s thought as possibly contributary to his final accusation and arrest, as many of its comedic themes uncannily echo the outcome of his trial. Others see this play as too obscure to create so huge a wave.

However you see it, The Clouds stands at a cross-roads very similar to our own. While Greek pre-Socratic philosophy was in many ways nearer to the speculations of early science than to philosophy, it still retained a sense of reverence for the Gods; but by the time of the play’s performance, people had begun to absorb new ideas that were leading to a sense of humanity’s evolution from primitive beginnings rather than seeing the cosmos as a gift of the gods. Our own era has emerged into a somewhat similar landscape, whereby popular belief now over-turns any dependence upon the Gods, and where spiritual respect has been jettisoned in the light of Darwinian evolution, while many now trust in the physical evidences of science as being a true representation of our cosmos.

The unfortunate result of accepting this narrow modern belief is that people tend to behave as if this life is all that we have, that this physical world all that exists, and that our actions are without significant consequence, which leads us straight into step 9 of the Golden Verses – acting without thought of the consequences. Hierocles makes clear that,

‘All who reasons rightly and who makes use of their Prudence is assisted by Courage in all good and praiseworthy actions. They are assisted by Temperance in the things that please the senses; and they are assisted in both by Justice. Thus, Prudence is the beginning of all virtues and Justice is their end, and in the middle are Courage and Temperance. For the faculty that weighs and considers all things by right reasoning and that seeks out what is right in every action is the habit of Prudence. It is the most excellent disposition of our rational being by which all the other faculties are kept in good order; so that our Will is brave, our Desire is temperate, while Justice, by correcting and amending all our devices and animating all our virtues, adorns our mortal humanity with the excessive abundance of virtue belonging to our immortal humanity.

It is originally from the divine spirit that the virtues radiate and diffuse themselves in the reasonable soul; it is they that constitute its form, its perfection and all its felicity. And it is from the soul that these virtues shine with a reflected ray on this irrational being – the mortal body – by a secret and hidden communication, to the end that all that is joined to the rational essence may be filled with beauty, with decency and with order.’ (GV X, 2-4)

That ‘secret and hidden communication’ to our mortal body and to our irrational soul comes from the immortal and rational soul like a concealed light that shines upon us, illuminating our actions and bringing us to consider their motivation as well as their consequences.

Damascius (462-538 CE), who was the last successor of the Platonic school, in describing the virtuous life of his own teacher, Isidore of Alexandria or Gaza (c.450-520 CE), reminds us once more of the different aspects of our nature: ‘He used to say that, just as the soul has three parts or types, so too there are three different ways of life, each of which contains all three elements while receiving its overall shape from the dominant one, which also gives it its name.

1. Reason is the main influence on the first of these, which could be called the life of Kronos, the golden race, or the generation akin to the gods, celebrated in the guise of myth by poets seated on the tripod of the Muse.

2. Emotion influences the second, which engages in wars and battles and generally fights for the first prizes and for glory. and which we continually hear talked about by history.

3. Appetite rules the third, which is totally dissipated, corrupted by unbridled wantoness, dominated by base and shrinking thoughts, associated with cowardice, wallowing in swinishness of every kind, avaricious and petty, desiring the security of a slave, achieving nothing noble or free, servile and weak, measuring happiness solely in accordance with the belly and the loins, totally without nobility of spirit; like a body dumped in a corner, lying enervated and incapable of movement. And he showed the life of the men who are now in the service of generation to be much baser even than this.’ (Section 18 from the Life of Isidore by Damascius.)

These three ways of life are, of course, dictated by our Reason, our competitive nature, and the sensations of our desire and passions. These are the three main arenas of self-moderation in any philosophic life where we seek to do our best to live ethically and considerately without being moved by irrational motivations that lead into crashing and burning.

CHOICE, PROVIDENCE AND WHAT IS UP TO US.

So how do we steer our soul in ways that uphold our purpose? Hierocles tell us,

‘From the use we make of our right reason it necessarily follows that we not behave ourselves rationally and foolishly in any of the accidents of this life that seem to us to happen without order. Instead, we must justify them generously by discovering exactly the causes of them, and support them with constancy, never complaining of the Beings who have the care of us and who, distributing to each person according to their merit what is due to them, have not bestowed the same rank and the same dignity on those who gave no proofs of the same virtue during their first life. For, seeing there is a Providence, and that the soul of humans is incorruptible by nature, and inclining either to virtue or vice voluntarily and of its own free choice, how can they who are the very Guardians and Keepers of the Law (i.e. the Oath), that requires everyone to be treated according to their merits, treat those that are in no way alike as if they were? And how can they do otherwise then distribute to each person the fortune which, it is said, each person at their coming into the world chooses for themselves according to the lot that has fallen into their share?

Therefore, it is not a fable that there is a Providence that distributes to each of us what is our due, and that our soul is immortal, it is evident that instead of accusing those Beings who govern us of our misfortunes, we ought only to blame ourselves. And that is the way to acquire a power and strength sufficient to heal and amend all our misfortune, as the following verses will teach us. For when we come to find the causes of this great inequality to be in ourselves, we shall, by sound judgements, alleviate the bitterness of all the accidents that happened to us in this life. And in the next place, by holy methods and by good reflections, stemming the tide of afflictions, we shall raise our past souls to what is most excellent and entirely deliver ourselves from the grievous ill we suffer.’ (GV X. 24-26)

But then how do we steer our lives in a world governed by factors and agencies like Fate, Necessity, Providence and human will that are continually weaving their unaccountable changes to our lives? HIerocles is leading us to look more closely at the wisdom we already possess – whether it is innate or recollected – by the light of the four cardinal virtues. The ancients had a helpful concept that will be become very useful to us in our own lives, and to which we can have recourse again and again. In Greek, this is called eph-hemin, better known to us as ‘what is up to us.’ By checking how much something is up to our choice or power, or whether it lies outside our power, we limit several of life’s problems. For it is in the exercise of our choice that can bring ourselves into the prison where freedom is lost, or else it enables us to remain true to the soul and be free.

We start small in this verse, with thoughtless actions. Epictetus unscores this from a Stoic perspective, ‘[It is needful] not to be foolish, but to learn what Socrates taught, the nature of things; and to not rashly to apply general principles to particulars. For the cause of all human evils is the not being able to apply general principles to special cases.’ (EP 4, 1)

Behaving sensibly is one thing, but anticipating what might accompany our actions also prevents us from expecting too much, but if we examine what lies within our power or ‘what is up to us’ and what lies beyond our power, we will not fall into the trap of resentment and self-betrayal. Epictetus gives us a very ordinary example to help us:

‘When you’re about to start any action, remind yourself about the kind of action that it is. So, if you’re going out to the public baths, set before you the things that happen at the baths: that people may splash you with water and jostle you in the water, that people may steal from you. And then you’ll be able to undertake the action in a sure way, if you say to yourself at the start, “I want to take a bath and to ensure, at the same time, that my choice remains in harmony with nature.” Just follow the same course in every action that you were intending to do. If anything gets in your way while you’re taking your bath, you’ll be ready to tell yourself, “well this wasn’t the only thing I wanted to do, but I also wanted to keep my choice in harmony with nature; and I won’t keep it so if I get annoyed at what is happening.” (EP Handbook 4)

Annoying things happen every day: the car breaks down on the morning you really need it early, the beloved plate that your dear aunt gave you is smashed by your dog leaping up enthusiastically to greet you, you cannot get a signal to phone home an important message, the bath-water you were so looking forward to entering grows cold because you had to deal with a persistent person on the phone. Yes, these are all instances of ‘stuff happening’ that none of us is immune from! We are not being specially selected to be personally zapped by life, and while the first defence of most humans is to blame and be annoyed at ‘those who let it happen to you’, we have to be careful that we don’t assign blame to the Gods. This is warning that comes to us from all quarters of philosophical understanding.

‘Don’t allow whatever is contrary to nature become another evil for you, for you were not born to share in the humiliations and misfortunes of others but in their good fortune. Whoever suffer misfortunes, you have to remember that they suffer this through their own fault, since God created all human beings to enjoy happiness and enjoy peace of mind. They have been provided with the resources to achieve this, giving some things to one to own, but not the same to others. The resources which are open to hindrance, distraint or compulsion are not our own, but all that is immune to hindrance is our own; and the nature of the good and bad which has been given to us, among all the things that our own, which is appropriate for the Gods who watch over us and protect us like a true guardian. (ED 3:241-3)

This is a point around which many people who resent any lack of divine interventions in their personal affairs: ‘why did God not save my child?’ Which soon leads to the plaint of ‘how can God be called good because so many bad things are allowed to happen?’ The failure to attend to cause and effect in, not just our current life, but also in our previous lives is something that few wish to consider.

§ Consider:

* What is your response to the Myth of Er? What have you deduced/remembered of any past lives of your own, however vestigial? How has that memory or experience shaped your present life? What aspects of incarnatory memory motivate you to follow a better way of life or to specific goals.

* Looking over the day you have just had, what lay in your power, and what was not within your power?

*Take this quotation from Francis Thompson’s poem The Mistress of Vision within you and become aware of the ripples that issue from any motivated action that you took this week:

‘All things by immortal power Near or far Hiddenly To each other linkéd are: That thou canst not stir a flower Without troubling a star.’

MEDITATION

We have reason to very much thank the Byzantine statesman, Photius (819-893) whose great library retained many books of the late Platonic period. Despite becoming Patriarch of Constantinople, his reverence for learning was such that he not only gave extracts of these Classical writings but also made abridgements of other important works, memory of which now only survive because of him.

In this meditation, Photius paints for us the Pythagorean universe, including the heavenly bodies which were seen as visible manifestations of the divine powers, the classical elements, as well as the evils which were seen to exist in sublunary or regions below the moon. In this sublunary region, which includes the earth itself, four causes operate – the Gods, Fate, the Choices which were made before our birth (‘our Election’) and Fortune or Luck. In the following passage, Photius reaches back 13 centuries to give us this early view of the universe:

‘Pythagoras taught that in heaven there are 12 orders, the first and most elevated being the fixed sphere where dwells the highest God, and the intelligible deities, and where Plato located his ideas. Next are the seven planets: Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, Mercury, Moon, and Sun. Then comes the sphere of fire, that of air, water, and last earth. In the fixed sphere dwell the first cause and whatever is nearest to it is the best organised and most excellent; well that which is furthest there from is the worst.

Constant order is preserved as low as the moon, while all things sublunary are disorderly. Evil, therefore, must necessarily exist in the neighbourhood of the Earth, which has been arranged as the lowest, as the basis for the world, and as a receptacle for the lowest things.

All supra-lunar things are governed in firm order, and providentially by the decree of God, which they follow; while beneath the moon operate four causes; God, Fate, our Election, Fortune. For instance, to go aboard ship, or not, is in our power; but the storms and tempests that may arise out of a calm, are the result of Fortune; and the preservation of the ship, sailing through the waters, is in the hands of Providence, of God. There are many different modes of Fate. There is a distinction to be made between Fate, which is determined, orderly and consequent, while Fortune is spontaneous and casual.

- Photius fragment, Pythagorean Source Book p.138

Thank you to Tyler Myles Lockett for kind permission to reproduce his image of the Spindle of Necessity here. For more about Tyler’s work, please follow this link; https://linktr.ee/tylermileslockett